History timeline ; 1640s - 31/08/1957

Independence of Malaya

North Borneo (Sabah): An annotated timeline 1640s - present.

March 1, 2013 | Filed under: Daily Dose, Events Mode and tagged with: Britain, Brunei,

byconstitution, diplomacy, Indonesia, North Borneo, Philippines, Sabah,

Sultanate of Sulu, Sulu, territory, UK, United Kingdom, USA

Edited by : Malay Archipelago Blog (Malaysia) -April 1, 2013

I am sharing a timeline I have compiled of key events and

accompanying literature on the North Borneo (Sabah) issue. This timeline is

being shared for academic and media research purposes. It is not being

published as an official statement of policy in any shape or form, nor does

this timeline purport to be representative of of the views of the Philippine

government.

Introduction

Introductory Material

B. On the heirs to the Sultanate of Sulu (unofficial)

Controversies on Succession to Sultanate of Sulu 1936-present

Controversies on Succession to Sultanate of Sulu 1936-present

Line Of Succession of Sulu Sultanate in the Modern Era

A Chart on the genealogy of the Modern-day Sultans of Sulu has been published in the official Gazette

A Chart on the genealogy of the Modern-day Sultans of Sulu has been published in the official Gazette

Introductory Concepts

Pre-16th century social system

Tagalog:

Nobility= Maginoo

Free Men = Timawa

Slaves = Alipin (2 subcategories: alipin namamahay,

performing personal service/ household chores; and alipin sagigilid, working

the fields)

Visayas:

Ruling class = Datu

Free Men = Timagwa

Slaves = Oripun (freedom regained either through money or

services rendered except for lubos nga oripun)

Mindanao:

Ruling Class = Datu

Non-Slave Followers = Endatuan (Obliged to provide the Datu

support in the form of scheduled payments of a portion of their crops and

unscheduled contributions for prestige feasts or bridewealth payments. They

were also required to perform military and nonmilitary labor service.)

Chattel slaves = Banyaga (Taken in raids or warfare or

purchased, were a common form for storing and investing surplus wealth)

Debt-slaves = Ulipun (Endatuan could be reduced to ulipun

for a number of causes, the rate of reduction often being related to the

availability and cost of banyaga at a given time. New debt-slaves were either

added to a datu’s personal following or put to work to produce food or provide

menial services to the datu’s household. Typically, a significant portion of a

datu’s debt-slaves were utilized as personal retinue or armed retainers and

were supported by banyaga or other debt-slaves.)

Sultanates: defined and described in McKenna, Thomas M.. Muslim rulers and rebels everyday politics and armed separtism in the southern Philippines. Berkeley : University Press, 1998. Print as follows :

[S]ultanates… conformed to a general sociopolitical type that has been characterized as a “segmentary state” (Southall 1965) or “contest state” (Adas 1981). They were loose confederations of local overlords, or datus. Datus formed a tribute-taking aristocracy with hereditary claims to allegiance from followers. While a ruling datu was almost always associated with a specific district, or inged,[5] the index of relative political potency was command of people rather than control of territory. In accord with the pattern that pertained throughout precolonial Southeast Asia, where arable land was more abundant and thus less valuable than human resources (Reid 1988), the wealth of a ruling datu was secured through rights over persons rather than rights in land.

[S]ultanates… conformed to a general sociopolitical type that has been characterized as a “segmentary state” (Southall 1965) or “contest state” (Adas 1981). They were loose confederations of local overlords, or datus. Datus formed a tribute-taking aristocracy with hereditary claims to allegiance from followers. While a ruling datu was almost always associated with a specific district, or inged,[5] the index of relative political potency was command of people rather than control of territory. In accord with the pattern that pertained throughout precolonial Southeast Asia, where arable land was more abundant and thus less valuable than human resources (Reid 1988), the wealth of a ruling datu was secured through rights over persons rather than rights in land.

…Because of the existence of a royal (barabangsa) bloodline,

the sultan was not simply a primus inter pares ruler. He was, nonetheless, a

datu who, as a result of a combination of pedigree and political savvy,

commanded the allegiance of other datus. That allegiance was accomplished and

maintained primarily through the creation of dyadic alliances between the

sultan and individual datus—arrangements commonly sealed either by his bestowal

of a daughter in marriage or his marriage to a daughter of another datu. Because

datus ruling ingeds were the basic components of a sultanate, the authority of

a sultan was exerted not over a royal domain as such but over his datu

supporters, linked together in a network of dyadic alliances.

Ruma Bechara: translated literarily as “House of Talk,” or

council of advisers, ratifies undertakings of the Sultan. The council[1] also

designates the Raja Muda or crown

prince, as well as the accession of a new sultan.

Origin of sultanate: Abu Bak’r was first Mindanao ruler to

adopt title of “sultan” (based on concept of Arab Caliphate); this is where

Hindu title of “rajah” is replaced with “sultan”

Sultans of Sulu descended from three distinct lines:[2]

Indigenous population (local princess): Established the

Sultans were not foreigners and could claim ownership of land.

Malaysian royalty: Strengthens legitimacy by being related

to dynasties that ruled Malaysia and were heirs to empires

Descendant of the Prophet Muhammad: right to rule over

Muslims

Tarsilas or salsilas – genealogies used by Islamic

royalty;[3] no datu or person can become a sultan unless he was a

tried-and-true descendant of the first sultan reflected on the tarsilas.

Immediate descendants of the first Sulu sultan who ruled are

called sultans in the tarsilas. A few succeeding ones are called Pangirans,

suggesting relationships with the royal family of Brunei.[4]

See also: H. Otley Beyer, Brief memorandum on the government of the Sultanate of Sulu and powers of the Sultan during the 19th century

Tributory Mode of Production: McKenna, Thomas M.. Muslim rulers and rebels everyday politics and armed separatism in the southern Philippines. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998. Print defines the economic system of the sultanates as

Tributory Mode of Production: McKenna, Thomas M.. Muslim rulers and rebels everyday politics and armed separatism in the southern Philippines. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998. Print defines the economic system of the sultanates as

[A] single political-economic system based on the external

acquisition of plunder and slave labor and the internal production of

commodities for external trade. It was a system propelled by the direct

extraction of surpluses from primary producers by political or military means,

and the circulation of that surplus “through the transactions of commercial

intermediaries”…

That system comprised two principal socioeconomic categories

that crosscut ethnolinguistic boundaries: tribute-takers and tribute-providers.

Tribute-providers were predominantly direct producers, either freemen or

slaves. Tribute-takers consisted primarily of local overlords (datus) linked

with one another through intermarriage, through patronage arrangements, and by

means of the ideology of nobility.

An Annotated Timeline (Unofficial)

Late 1300s – Early 1400s (Raiding, Trading, and Feasting by

Laura Lee Junker)

Tributary trade missions occur from the Philippines these

trade missions compete for Chinese trade attention .

Early 1400s (Raiding, Trading, and Feasting by Laura Lee

Junker)

Southern Philippine polities (Maguindanao, Sulu, and

Kumalalang) were competing for dominance along the Southern South East Asia

trade routes.

1417 (Raiding, Trading, and Feasting by Laura Lee Junker)

An initial trade mission successfully launched the Sulu

polity as a significant player in early Ming southern spice trade.

1450

Sultanate established among the Islamized people of Sulu[5]

Thomas McKenna (2002) in Muslim Rulers and Rebels points

out:

Term ‘sultanate’ refers to a political institution based on

an Islamic legitimating ideology and headed by a sultan who is a formally

hereditary leader who possesses the authority to bestow titles and appoint

individuals to specialized subordinate offices. Sultans were distinguished by

their pulna status (those designated as pulna were able to trace direct

ancestry from Sarip Kabungsuwan through both parents). Within the datu estate,

claims to status rank were predicated upon the quality and quantity of ties

linked to Sarip Kabungsuwan. It was a complex system of rank and status; an

example of which is the Cotabato Sultanate that had neither the number of

offices of the Sulu Sultanate nor the elaboration in rank titles found among

the Maranao. The Maguindanao Sultanate for instance, was known to have 11

offices (including that of the Sultan), arranged in 3 orders of rank.

Canoy: With this difference: unlike Tagalog/ Visayans, where

leadership was chosen on basis of “age, wisdom or magical powers” leadership in

Mindanao was picked for “bravery and skill as warriors”; succession to throne

based on prowess rather than lineage; conflicting claims settled either through

combat or decision by elders

1640s

Spain signed peace treaties with the strongest sultanates,

Sulu and Maguindanao, recognizing their de facto independence.[6]

April 14, 1646

Treaty signed between Sultanate of Sulu and Spain regulating

recognition of succession in sultanate and respective territory and rights of

Spain and Sultanate of Sulu.[7]

1675-1704

Sultan of Sulu became sovereign ruler of most of North

Borneo by virtue of a cession from the Sultan of Brunei whom he had helped in

suppressing a rebellion.

There is no document stating the grant of North Borneo from

Sultan of Brunei to Sultan of Sulu, but it is accepted by all sides.[8]

Eighteenth-century officers of the British East India

Company had taken the cession for granted and dealt with the Sulu Sultans as

the sovereigns of Sabah.

Jesse, Brunei resident for the Company in 1774, and

Sir Stamford Raffles did not raise questions about the cession of Sulu by the

Brunians.[9]

Autonomous States and Colonies 1792-1860

1737

Treaty of alliance between Spain and the Sultan of Sulu,

Azim Ud-Din (son of sultan Bagar Ud-Din; became sultan in 1735)[10]

1742

Treaty of alliance between Spain and Sultan Azim Ud-Din

invoked by Sulu.[11]

1745

Treaty of alliance between Spain and Sultan Azim Ud-Din also

invoked in effort of Sultan Azim Ud-Din to consolidate control of North Borneo

territories against Tiruns (indigenous inhabitants of North Borneo)[12]

1758

Alexander Dalrymple envisages creation of “vast emporium of

trade” for English, Indian, and Chinese goods in Borneo-Sulu vicinity. Receives

permission from Governor Pigot to go on mission of exploration:

To open trade with Sulu

Survey and make hydrographic notes on North Borneo

Survey and make hydrographic notes on North Borneo

Negotiate treaty with Sultan of Sulu [13]

January 28, 1761

Alexander Dalrymple, Deputy Secretary of the Madras Council

of the East India Company signs Articles of Friendship and Commerce with Sultan

of Sulu Muiz-ud-din Bantilan granting land for a factory; granting

extraterritorial legal rights to the English; granting trade monopoly to

British; and establishing alliance[14]

Governor Pigot and the Madras Council of the East India

Company sends Dalrymple to Sulu, along with one Thomas Kelsall, to announce the

formal acceptance of the Treaty and to obtain the cession of Balambangan

island.[15]

In the same year, Articles of Friendship and Commerce

between the Sultanate of Sulu and Alexander Dalrymple are ratified by the Ruma

Bichara

September 12, 1762

Sultanate of Sulu cedes the island of Balambangan to British

East India Company

October 1762

Prior to the British occupation of Manila, the Secret

Committee of the British East India Company wanted to take possession of

Mindanao.[16]

The English forces in Manila encountered and released Sultan

Alim-ud-din and his son Raja Muda Muhammed Israel (who had been taken

captive)–in gratitude, the Sultan made “generous offers” to the Manila Council.

Deputy Governor Dowsonne Drake and his council agreed to conclude a treaty that

would not be in conflict with the 1761 treaty.

January 23, 1763

Dalrymple hoists the British flag in Balambangan, after

entering into a treaty with the new

Sultan Alim-ud-din I, son of Bantilan, for the cession of Balambangan.[17]

February 23, 1763

A Treaty of Alliance and Commerce is signed between Sultan

Alimudin I and Dowsonne Drake. It confirmed the 1761 treaty, including the

mutual defensive alliance, except for a provision stating British respect of

the government, customs and religion of the people of Sulu.[18]

1762-1764

British occupation of Manila and extensive parts of Northern

Luzon.

During this period, Sultan Alimuddin is a prisoner in

manila; his nephew reigns as Sultan Alimmudin II, temporarily in his uncle’s

absence until May 17, 1764

It is during this period of captivity that Alimuddin:

Offers to sign treaty with British East India Company;

Reassures Spanish Governor General that this is meaningless

because he hasn’t assumed powers of sultan.

September 19, 1763

Dalrymple receives a confirmation of the cession of

Balambangan from Sultan Alimuddin II, son of Bantilan.[19]

May 21, 1764

Spanish reassume control of Manila. Sometime after this,

Alimuddin ratifies the cession of Balambangan Island to the British East India

Company and ratifies a new Treaty of Commerce and Friendship with Dalrymple

June 29, 1764

Sultan Alimudin I confirmed the cession of North Borneo

(from the northeast side of the river Kinabatagan to the northwest side of the

river Kimanis, together with Balambangan, Labuan, Banguey and Palawan) to the

East India Company in return for the promise that one of his sons, Datu

Saraphodin, was to govern these territories.[20]

July 2, 1764

Sultan Alimudin II signed the deed of cession, together with

Datu Oranky Mamanacha, Datu Tumangoon, and Datu Mannabeel on behalf of the

nobility in Sulu.[21]

July 30, 1764

Dalrymple granted a commission to Datu Saraphodin (one of

Sultan Alimudin I’s sons), vesting the power and authority to assume government

of the ceded territories on behalf of the Company.[22]

September 28, 1764

A perpetual treaty of friendship and commerce was signed by

the Sultan of Sulu and Dalrymple which renewed and confirmed the 1761

treaty.[23]

1769

The East India Company decides to occupy Balambangan and

make it a strategic commercial base; however, the conditions on the island lead

them to abandon this settlement in early 1755.[24]

1800–1850

This area (a portion of the territory ceded to Sulu by

Brunei) had been effectively controlled by the Sultanate of Bulungan in

Kalimantan, reducing the boundary of Sulu territory in North Borneo to a cape

named Batu Tinagat and Tawau River. (United Nations Publications)

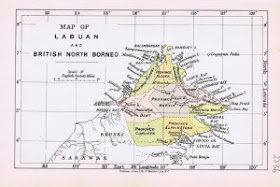

Map showing Tawau river and Kalimantan.

1803-1805

The East India Company attempts to re-occupy Balambangan but

is unsuccessful due to the Company’s Directors’ disapproval.[25]

1805-1858

The East India Company “showed no interest in resettling

North Borneo”.[26]

March 17, 1824

Treaty of London signed by the Netherlands and Great

Britain.

Allocates certain territories in the Malay archipelago to

the United Kingdom and the Netherlands (Dutch East Indies).[27]

Detail of 1822 C.G. Reichard Map outlining Sultanate of Sulu

in blue.

September 23, 1836

Treaty of Peace and Commerce between Spain and Sulu, signed

in Sulu

Granting Spanish protection of sultanate, mutual defense,

and safe passage for Spanish and Joloan ships between ports of Manila,

Zamboanga, and Jolo.[28]

Ortiz: Spain did not claim sovereignty over Sulu, but merely

offered “the protection of Her Government and the aid of fleets and soldiers

for wars…”[29]

February 5, 1842

An Agreement was made between the Sultan of Sulu and the

United States.

The agreement stated that the Sultanate of Sulu will protect

American vessels in the area should they be shipwrecked and protection of U.S.

citizens. The agreement was not subject to ratification and not proclaimed.[30]

April 23, 1843

French warship favorite arrives in Jolo soon after vessels

commander T.F. Page enters into treaty of Friendship and Commerce with Sultan

Pulalon

February 21, 1845

Ruma Bechara agrees to sale of Basilan to France for 100,000

Mexican dollars on condition it is occupied by France within 6 months. Spanish

Governor in Zamboanga protests. Governor General Narciso Cleveria orders

construction of fort in Pangasaha, Basilan as deterrent to France. France

eventually decides against purchase of Basilan.

1845

Muda Hassim, Uncle of the Sultan of Sulu, publicly announced as successor to the

Sultanate of Sulu with the title of Sultan Muda: he was also the leader of the

“English party,” (today the term for Crown Prince is Raja Muda)[31]

The British Government appoints James Brooke as a

confidential agent in Borneo[32]

The British Government extends help to Sultan Muda to deal

with piracy and settle the Government of Borneo[33]

April 1846

Sir James Brooke receives intelligence that the Sultan of

Sulu ordered the murder of Muda Hassim, and some thirteen Rajas and many

of their followers; Muda Hassim kills himself because he

found that resistance is useless. [34]

July 19, 1846

Admiral Thomas Cochrane, Commander-in-chief of East Indies

and China Station of the Royal Navy, issued a Proclamation to cease hostilities

(“piracy,” crackdown versus pro-British faction) if the Sultan of Sulu would

govern “lawfully” and respect his engagements with the British Government

If the Sultan persisted, the Admiral proclaimed that the

squadron would burn down the capital of the sultanate.[35]

May 7, 1847

James Brooke is instructed by the British Government to

conclude a treaty with the Sultan of Brunei

British occupation of Labuan is confirmed and Sultan

concedes that no territorial cession of any portion of his country should ever

be made to any foreign power without the sanction of Great Britain[36]

December 1848

James Brooke, British Governor of Labuan and Consul General

in North Borneo, established preliminary contact with the Sultan of Sulu

May 28, 1849

James Brooke and Sultan Pulalon of Sulu agreed on favored

nation status for each other; right of British subjects to acquire properties

in Sulu; docking rights; pirate-free policy and prior consent before.

Brooke then, proceeds to Zambaonga to inform Spain. The

Spanish object

May 29, 1849

Convention of Commerce between Britain and the Sultanate of

Sulu

Sultan of Sulu will not cede any territory without the

consent of the British. [37]

November 12, 1850

The Dutch signed a Politiek Contract with the Sultan of

Bulungan as noted in “Affaire relative à la souveraineté sur Pulau Ligitan et

Pulau Sipadan”. See pertinent excerpts (unofficial translation)[38]:

In 1850, the Government of the Dutch East Indies and the

sultans of the three kingdoms [belonging to a “contrat de vassalité”] agreed on

the respective kingdoms they were given in fief. The agreement with the Sultan

of Bulungan is dated November 12, 1850.

A geographical description of the area constituting the

Sultanate of Bulungan appeared for the first time in the contract of November

12, 1850. Article 2 of the contract described Bulungan territory as follows:

Bulungan territory is limited by the boundaries as follows:

With-Gounoung Tabur: the coast to the interior, the river

Karangtiegau from its mouth to its source, in addition, the boat Beoukkier and

Mount Palpakh.

With the following belonging to sulu: the sea cape Tinagat

referred to as Batou and the Tawau river

The following islands belong to Bulungan: Terrakan, Nanukan,

and Sebatik, with small islands attached to it.

This delineation is based on a provisional basis and will

result in a new comprehensive review and redetermination.

Circa 1850: Spheres of British and Dutch influence in

Borneo; territories of Sultans of Brunei and Sulu, including territory of

Sultan of Sulu placed under control of Sultan of Bulungan, and ceded in turn,

to Dutch

East Indies by Sultan of Bulungan

Treaty signed with Spain by the Sultan of Sulu, Mohammed

Pulalun.

The Sultanate of Sulu was incorporated into the Spanish

Monarchy.[39]

1854-1858 German Map showing extent of Spanish dominion in

the Philippines: see wavy line excluding portion of Palawan and Sulu

1858

The East India Company is dissolved following the Indian

Mutiny, and all its territories are taken over by the British Crown.[40]

1860

Spanish government, concerned over German trade in guns

ammunition and strategic materials with Moros, proclaims ban on foreign trade

with Sulu

August 11, 1865

Claude Lee Moses, an “American adventurer with dubious

consular status,” secures from the Sultan of Brunei and the Pengeran Tumonggong

a 10-year lease of a tract of land north of Brunei, with rights and privileges

similar to those vested upon Rajah James Brooke in Sarawak, for an annual

payment of M$9,500.[41]

September 9, 1865

Moses transfers all rights to American businessmen Joseph W.

Torrey and Thomas B. Harris, in return for a promise to pay him later.[42]

October 25, 1865

Torrey and Harris, with two Chinese associates, sign an

agreement to take over the cession, raise a capital of $7,000, and conduct

trade between North Borneo and Hong Kong. They then organized the American

Trading Company of Borneo.[43]

November 1865

The American Trading Company settles in North Borneo. Torrey

is given the title “Raja Ambong and Marudu” by the Sultan of Brunei[44]

Following Harris’ death in 1866 and lack of capital, Torrey

approaches Baron Gustavus von Overbeck in Hong Kong (a German who served as a minor diplomatic

official of the Austro-Hungarian Empire) to propose acquisition of the lease

territory In turn, Overbeck initially planned to sell the territory to the

Austro-Hungarian Empire.

July 30, 1866

Moses writes the U.S. Secretary of State saying the property

he acquired was a lease.

In the letter: “On the 9th day of September I transferred my

leases to a company styled the American Trading Company of Borneo, J. W.

Torrey, President”[45]

January 17, 1867

that, whatever Treaty rights Spain may have had to the

sovereignty of Sulu and its dependencies, those rights must be considered as

having lapsed owing to the complete failure of Spain to attain a de facto

control over the territory claimed.

The High Colonial Age 1870-1914

Section of 1874 Colton’s East Indies and Strait of Singapore

Map

Section of Colnton’s 1874 Map: Territory of “Sultan of

Sooloo”

1872

1872-1914: evolution of modern-day delineations of territory

in Borneo. Expansion of Sarawak, reduction of Brunei, creation of State of

North Borneo and absorption by Dutch East Indies of portion formerly

administered by Sultan of Bulungan, all from territory of Sultan of Sulu

July 11, 1874

Baron Overbeck signs an agreement with Count Montgelas and

A.B. Mitford to acquire the rights from the American Trading Company, where he

will put £2,000 and they will put up £1,000 each. Torrey sells all his rights

to in the American Trading Company to Overbeck for $15,000 on the condition

that the lease (which was due to expire that year) be renewed.[46]

However, the Sultan of Brunei did not want to renew it

because neither Moses nor Torrey had paid the Sultan during the contractual

period.

1874

These maps show the extent of the territory of the Sultan of

Sooloo (Sulu)

June 21, 1875

Renewal of the lease for another 10 years, upon payment of

£1000 to the Pengeran Tumonggong.[47]

1876

Two German vessels that break Spanish blockade are captured

by Spain. Germany and Britain protest.

Spanish government launches Malcampo expedition against

Sulu.

Overbeck approaches Alfred Dent, who realizes the potential

of North Borneo and advances £10,000 on condition that the sole management of

the North Borneo Concession be given to him.[48]

February 2, 1877

Ordinance issued in the form of Statute (Decree) No. 31 on

the power set who oversees the royal Bulungan Tidung Land, the island of

Tarakan, Nunukan, Sebatik Island, and some small islands in the vicinity. In

fact, the Decree will be confirmed again on March 15, 1884 by the Secretary of

the Dutch East Indies in Bogor.

May 30, 1877

Protocol of Sulu signed between Spain, Germany, and Great

Britain, providing free movement of ships engaged in commerce and direct

trading in the Sulu Archipelago.

British Ambassadors in Madrid and Berlin were instructed

that the protocol implies recognition of Spanish claims over Sulu or its

dependencies.

At this point the following western countries have possessions

in Southeast Asia:

British = Singapore, Malaya, Brunei, Sarawak, and North

Borneo

Germany = Papua New Guinea

Netherlands = Indonesia

Spain = Philippines, Guam, Marshall Islands, Caroline

Islands

France = Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia (French IndoChina)[49]

December 1877

Expeditions of Alfred Dent to control north part of Borneo

began.

Alfred Dent, member of the commercial house of Dent Brothers

and Co. of London. [50]

Overbeck obtains a grant from the Sultan of Brunei for some

28,000 square miles of land in the northern part of Borneo for an annual

payment of $15,000. Overbeck learns afterward that the northeastern part of

Borneo was ceded to the Sultan of Sulu, and so he and William H. Treacher sail

to Sulu to negotiate a contract for the rest of North Borneo.[51]

Quiason: Upon close scrutiny and extensive research, based

on Professor K. Tregonning’s book ‘Under Chartered Company Rule’, the use of

the term “cession” in those days actually meant “lease” that is, the lease of a

territory for a stipulated period of time in consideration of an annual

payment.

January 2, 1878

Acting Consul-General Treacher sends repor: Overbeck will

have to conclude separate contract with Sultan of Sulu:

The Sultan of Brunei’s territory extends, at the utmost,

only to the west side of Malludu Bay, though formerly the Brunei kingdom

extended as far as Cape Kaniungan, on the east coast, in latitude 1° north. The

remaining territory, mentioned in the grants is actually under Sulu rule, and

occupied by Sulu Chiefs, and it was only because the districts were mentioned

in the original American grants that they are again included, and Mr. Overbeck

will now have to make a separate agreement with the Sultan of Sulu for them.

January 22, 1878

Sir Alfred Dent obtains sovereign control over the northern

part of Borneo for 5,300 ringgit ($5,000) from the Sultans of Brunei and

Sulu. See contending translations of

relevant portions of this document.See also the Spanish translation. See

another English translation.

Concessions would later be confirmed by Her Majesty’s Royal

Charter in November, 1881 granted to the British North Borneo Co.

On the Charter granted, Professor George Mct. Kahin states

“the non-alienation principle was explicit; there could be no transfer of

territory without the consent of the British Secretary of State” and that

should a conflict arise, the British Secretary of State would have the power of

decision

The territory of the Sultan of Sulu over the island of

Borneo:

commencing from the

Pandassan River on the north-west coast and extending along the whole east

coast as far as the Sibuco River in the south and comprising amongst other the

States of Paitan, Sugut, Bangaya, Labuk, Sandakan, Kina Batangan, Mumiang, and

all the otherterritories and states to the southward thereof bordering on

Darvel Bay and as far as the Sibuco river with all the islands within three

marine leagues of the coast.[52]

Sultan of Sulu Mohammed Jamalul Alam appoints Baron de Overbeck

as Datu Bendajara and Raja of North Borneo.

(Baron de Overbeck, Austrian national heavily connected with

the house of Dent and Co. at Hong Kong. Overbeck was sent to Borneo as a

representative of Dent and Co. to enter negotiations with Sultans and Chiefs of

Brunei and Sulu – Dec 1878 Statement and Application of Debt of Dent and

Overbeck to the Marquis of Salisbury)[53]

Sultan of Sulu Mohammed Jamalul Alam (Translation of Deed of

1878 by Prof. Harold Conklin) wrote letters to the Governor of Jolo, Carlos

Martinez and the Captain-General

Malcampo to revoke what he termed the lease he granted over North Borneo.[54]

See: Report to Earl of Derby from Acting Consul-General

Treacher:

By this grant, in consideration of the annual payment to the

Sultan of the sum of 5,000 dollars, the representatives of the proposed Company

obtain the concession of the country extending from the Pandassan River on the

west coast to the Sibuco River on the east, including the five harbours of

Maludu and Sandakan, and Darvel and Sibuco Bays

.

The Sultan was anxious that the limits should be fixed from

Kimanis to Balik Pappan, explaining that by making no mention of the country

from Kimanis to Maludu he might be thought by his people to be abandoning his

claim to it, though at the same time he acknowledged that his power actually

only commences at Maludu, and that consequently he would ask no additional

rental if the limits were fixed as he desired; it being considered, however,

that complications might arise in the future with the actual possessors of that

country—for the most part independent Chiefs—a compromise was effected and the

limits fixed from the Pandassan River to the Sibuco River, the latter limit

being, according to a Dutch official chart, in the Baron’s possession, the northern

limit of Dutch territory on that coast, though, as I have not with me the

Treaty said to exist with Holland confining its right to colonize in these seas

within certain limits, I am unable to state whether they are justified in

coming so far north on that coast.

The Sultan assured me that at the present moment he receives

annually from this portion of his dominions the sum of 5,000 dollars, namely

300 busings of seed pearls from the Lingabo River alone, which at 10 dollars a

busing comes to 3,000 dollars per annum, and about 2,000 dollars from four

birds’-nest caves in the Kinabatangan River, which are his family possessions.

See contract in Spanish, in English (translation of

Spanish); Conklin translation (from Arabic copy in Washington); Maxwell and

Gibson translation.

April 4, 1878

Letter of Commanding General of the Naval Station of the

Philippine Islands: reporting Overbeck undertaking.

June 2, 1878

New contract of vassalage concluded between the Government

of the Dutch East Indies and the Sultan of Bulungan.

July 4, 1878

The Sultan of Sulu Mohammed Jamalul Alam sends a letter to

the Captain-General of the Philippines.

According to the letter of the Sultan, Sandakan was not

ceded to the United Kingdom but was only leased. The Sultan added that he only

did this under the threat of attack from the British.[55]

July 22, 1878

Bases of Peace and Capitulation signed in Jolo.

Sultan of Sulu, Mohammed Jamalul Alam declared the

sovereignty of Spain over the Archipelago of Sulu and its dependencies while granting

free exercise of religion and customs for his people. [56]

See also letter of July 24, 1878 from the Governor of Sulu

to Baron de Overbeck.

British, German, French, Dutch, and the Spaniards agree on

their spheres of influence in Southeast Asia.[57]

Peace treaty of Spain and Sultanate of Sulu.

Having signed peace treaty with Sultanate of Sulu, Spain

embarks on Spanish protocol to resume trade:

1. Sultan and Datus to receive salaries from Spanish

government; authorized to issue licenses for firearms and collect customs

duties on foreign trade except in ports controlled by Spain; Spain to respect

Islamic culture and religion and Sultanate to accept Christian missionaries.

2. Sultanate of Sulu

accepts sovereignty of Spain and concedes that no territorial cession of any

portion should ever be made to any foreign power without the sanction of Spain.

As a consequence of treaty, Spain efforts in sovereignty in

North Borneo.

Sultan of Sulu writes to Governor-General of the

Philippines: due to treaty, it is his will to cancel the contract in North

Borneo. The Sultan of Sulu also writes

to Governor of Sulu with same information.

Governor of Sulu writes to Overbeck: informing him of

cancellation of contract.

July 24, 1878

Governor of Sulu writes to Overbeck: contract with Sultan of

Sulu must be taken in context with preexisting treaties and Spanish

sovereignty. Overbeck responds to Governor of Sulu: Spanish protectorate over

Sulu does not nullify contract.

August 20, 1878

Governor-General of the Philippines writes to Madrid:

efforts to have Overbeck contract cancelled.

October 18, 1878

Contract between the Government of the Dutch East Indies and

the Sultan of Bulungan was approved and ratified by the Governor General of the

Dutch East Indies.

December 2, 1878

Dent and Overbeck apply for a Charter of Incorporation from

Queen Victoria.[58]

April 16, 1879

Acting Governor Treacher writes to the Colonial Office, objecting

to hoisting of Spanish flag over North Borneo. Treacher also writes to Sultan

of Sulu reiterating objection.

October 15, 1879

Acting Consul-General Treacher to the Marquis of Salisbury:

on whether Palawan included in Sultanate of Sulu, and reporting Spanish efforts

to have Sultan of Sulu hand over North Borneo to Spain.

November 5, 1879

Memorandum by the Duke of Tetuan to the Marquis of

Salisbury. See also Memorandum issued in Madrid, giving Spanish view on

Overbeck.

November 6, 1879

Mr. West to the Marquis of Salisbury.

1880

The sultanate’s territory became officially part of the

Dutch East Indies.[59

]

November 1, 1881

Queen Victoria grants Charter of Incorporation to the

British North Borneo Company.

British North Borneo Company now does actually exist “as a

Territorial Power” and not “as a Trading Company.”[60]

November 16, 1881

Spaniards protest granting of Royal Charter.

By virtue of treaties of capitulation of 1836, 1851, and

1878, Spain exercised sovereignty over Sulu and its dependencies including

North Borneo; Sultan of Sulu had no right to enter into any treaties or make

any cessions whatsoever.[61]

Drawn by W.M. Crocker, representative of British North

Borneo Company

W.J. Turner 1881 Royal Geographical Society Map: Drawn by

W.M. Crocker, representative of British North Borneo Company for 16 years.

Compare to 1901 and 1902 maps to see ultimate adjustments of various borders.

(map located by Roel Balingit)

W.J. Turner 1881 Royal Geographical Society Map, detail.

W.J. Turner 1881 Royal Geographical Society Map, inset map

showing general divisions of North Borneo. Portion in purple marked British

North Borneo Co. is what is generally identified as Sabah (North Borneo).

Portion in yellow, also marked “Sultan of Sulu” in this map, generally

comprises the portion of the Sultan of Sulu’s territory originally administered

by the Sultan of Bulungan, but which the Sultan of Bulungan in turn ceded to

the Dutch East Indies. Compare to 1901 Map to see further adjustments of borders.

January 7, 1882

British Foreign Minister Lord Earl Granville’s letter

saysCrown assumes no dominion or sovereignty over the territories occupied by

the Company, nor does it purport to grant to the Company any powers of

Government thereover.

Crown merely recognizes the grants of territory and the

powers of government made and delegated by the Sultans in whom the sovereignty

remains vested. [62]

1884

March 7, 1885

Spanish claims to Borneo abandoned by Protocol of Sulu

entered into by England, Germany and Spain.

Spanish supremacy over the Sulu Archipelago was recognised

on condition of their abandoning all claim to the portions of Northern Borneo

which are now included in the British North Borneo Company’s concessions.[63]

May 12, 1888

While civil war was ongoing in Sulu, “State of North Borneo”

is made a British protectorate.

An agreement between the British North Borneo Company and

Great Britain; British Government admits the North Borneo Company derived its

rights and powers to govern the territory.[64]

On the protectorate status of North Borneo, Professor Kahin

notes that “in effect, a status alreadyde facto was thereby rendered de jure.”

June 14, 1888

British Protectorate established over Sarawak.[65]

September 17, 1888

Blumentritt’s Ethnological Map of the Philippines, 1890

Detail of 1890 Rand McNally Map delineating Sultanate of

Sulu (yellow) from Spanish Philippines (green)

November 1, 1888

Royal Charter granted to British North Borneo Company:

5. In case at any time any difference arises between the

Sultan of Brunei or the Sultan of Sooloo and the Company, that difference

shall, on the part of the Company, be submitted to the decision of our

Secretary of State, if he is willing to undertake the decision thereof.

1892

Jose Rizal proposes to the Spanish government to establish a

Filipino colony in Sabah. This plan, however, does not push through.

1893 Netherlands Map indicating Borneo-Sulu Nautical Border

1893

The declaration of the contract of vassalage in 1878 between

the Government of the Dutch East Indies and the Sultan of Bulungan was amended.

1896

Federated Malay States

Provinces included:

Negeri Sembilan

Pehang

Perak

Selangor[67]

1894-1936

Sultan Jamalul Kiram II rules the Sultanate of Sulu.

Philippine Dependencies up to 1898: Marianas, Carolines,

Palau Islands, from information in The Philippine Islands by John Foreman

Actual Spanish Map

Treaty of Paris 1898

Spain cedes the Philippine Islands to the United States of America. The treaty lines did not include North Borneo (Sabah). [68]

Treaty of Paris

January 1899

President Emilio Aguinaldo wrote a letter to the Sultan of

Sulu pledging that the newly created Philippine Republic would “respect

absolutely the beliefs and traditions of each island in order to establish on

solid bases the bonds of fraternal unity demanded by our mutual interests.”

Aguinaldo was asking the Sultan for his support but

clarified that the Sultanate of Sulu was part of the Philippine Republic.

The Sultan of Sulu did not respond to President Aguinaldo’s

letter.[69]

May 1899

At the end of May, 1899, after the war had begun and

American troops posted to Jolo, the President’s cousin, Baldomero Aguinaldo,

who has been placed in command of the “Southern Region” of the Republic, wrote

the Sultan, “authorizing” him to … “establish in all… … of Minadanao and Sulu a

government in accordance with decrees of the Republic.” He was also requested

to report the number of his forces and the results of his efforts. The Sultan

of Sulu and other Moro leaders ignored him.

(Tan, Samuel K. “Revolutionary Inertia in Sulu,” The

Philippine Revolution and Beyond, Vol. II.)

February 1, 1899

U.S. President replies to Senate query, that payments to

Sultan of Sulu will come from Philippine Treasury.[70]

May 19, 1899

Captain E.B. Pratt with two battalions of 23rd infantry

arrive at Jolo – Sultan issues favorable proclamation.[71]

July 3, 1899

Gen. Otis orders Gen. John C. Bates to visit Sulu

archipelago with a view to a treaty.[72]

August 20, 1899

Kiram-Bates Treaty signed.

Treaty acknowledged the “sovereignty of the United States

over Jolo and its dependencies.”

December 5, 1899

In his State of the Union Message, William McKinley

discusses American policy towards the Sultanate of Sulu:

The authorities of the Sulu Islands have accepted the

succession of the United States to the rights of Spain, and our flag floats

over that territory.

On the 10th of August, 1899, Brig. Gen. J. C. Bates, United

States Volunteers, negotiated an agreement with the Sultan and his principal

chiefs, which I transmit herewith. By Article I the sovereignty of the United

States over the whole archipelago of Jolo and its dependencies is declared and

acknowledged.

The United States flag will be used in the archipelago and

its dependencies, on land and sea. Piracy is to be suppressed, and the Sultan

agrees to co-operate heartily with the United States authorities to that end

and to make every possible effort to arrest and bring to justice all persons

engaged in piracy. All trade in domestic products of the archipelago of Jolo

when carried on with any part of the Philippine Islands and under the American

flag shall be free, unlimited, and undutiable. The United States will give full

protection to the Sultan in case any foreign nation should attempt to impose

upon him. The United States will not sell the island of Jolo or any other

island of the Jolo archipelago to any foreign nation without the consent of the

Sultan. Salaries for the Sultan and his associates in the administration of the

islands have been agreed upon to the amount of $760 monthly.

Article X provides that any slave in the archipelago of Jolo

shall have the right to purchase freedom by paying to the master the usual

market value. The agreement by General Bates was made subject to confirmation

by the President and to future modifications by the consent of the parties in

interest. I have confirmed said agreement, subject to the action of the

Congress, and with the reservation, which I have directed shall be communicated

to the Sultan of Jolo, that this agreement is not to be deemed in any way to

authorize or give the consent of the United States to the existence of slavery

in the Sulu archipelago. I communicate these facts to the Congress for its

information and action.

February 1, 1900

Kiram-Bates Treaty submitted to the U.S. Senate by William

McKinley:

In compliance with the resolution of the Senate of January

24, 1900, I transmit herewith a copy of the report and all accompanying papers

of Brig-Gen. John C. Bates, in relation to the negotiations of a treaty or

agreement made by him with the Sultan of Sulu on the 20th day of August, 1899.

I reply to the request and said resolution for further

information that the payments of money provided for by the agreement will be

made from the revenues of the Philippine Islands, unless Congress shall

otherwise direct.

Such payments are not for specific services but are a part

consideration due to the Sulu tribe or nation under the agreement, and they

have been stipulated for subject to the action of Congress in conformity with

the practice of this Government from the earliest times in its agreements with

the various Indian nations occupying and governing portions of the territory

subject to the sovereignty of the United States.

Not ratified by the U.S. Senate, President Theodore

Roosevelt abrogates treaty.[73]

March 24, 1900

In an article published on the Evening Star entitled “Jolo

Jollities”, the author Theodore wrote that the Sultan of Sulu was honored with

a 17-gun salute upon boarding an American vessel and was familiar with the

honors rendered.[74]

November 7, 1900

Convention of 1900

Consolidate the American possessions in the Sulu archipelago

by including the islands of Sibutu and Cagayan, both of which had always formed

part of the possessions of the Sulu sultanate.[75]

British North Borneo Company obtains from Sultan of Sulu

even more territory.

Philippines, Borneo: 1901 London Atlas

December 3, 1900

In his State of the Union Message, William McKinley provides

details on the Convention of 1900:

I feel that we should not suffer to pass any opportunity to

reaffirm the cordial ties that existed between us and Spain from the time of

our earliest independence, and to enhance the mutual benefits of that

commercial intercourse which is natural between the two countries.

By the terms of the Treaty of Peace the line bounding the

ceded Philippine group in the southwest failed to include several small islands

lying westward of the Sulus, which have always been recognized as under Spanish

control. The occupation of Sibutd and Cagayan Sulu by our naval forces elicited

a claim on the part of Spain, the essential equity of which could not be

gainsaid. In order to cure the defect of the treaty by removing all possible

ground of future misunderstanding respecting the interpretation of its third

article, I directed the negotiation of a supplementary treaty, which will be

forthwith laid before the Senate, whereby Spain quits all title and claim of

title to the islands named as well as to any and all islands belonging to the

Philippine Archipelago lying outside the lines described in said third article,

and agrees that all such islands shall be comprehended in the cession of the

archipelago as fully as if they had been expressly included within those lines.

In consideration of this cession the United States is to pay to Spain the sum

of $100,000.

A bill is now pending to effect the recommendation made in

my last annual message that appropriate legislation be had to carry into

execution Article VII of the Treaty of Peace with Spain, by which the United

States assumed the payment of certain claims for indemnity of its citizens

against Spain. I ask that action be taken to fulfill this obligation.

Palawan, Sulu, Borneo Border, 1901 London Atlas

George Cram 1902 Borneo Map

Borneo, Palawan, Sulu, Spratleys: George Cram Map, 1902

December 1, 1902

The “Sultan of Sulu: a Musical Comedy” by George Ade and

Alfred Wathall opens in Boston.76]

December 20, 1902

The “Sultan of Sulu: a Musical Comedy” by George Ade and

Alfred Wathall is staged at Broadway’s Wallack’s Theatre.[77]

April 22, 1903

Additional $300 a year paid for a Confirmatory Deed stipulating

that certain islands not specifically mentioned in the Deed of 1878 had in fact

been always understood to be included therein.[78]

May 1903

The musical on the

Sultan of Sulu is published as “Sultan of Sulu: An Original Satire in Two Acts”

(by George Ade) in New York by Robert Howard Russell[79]

December 16, 1903

Leonard Wood Governor of the Moro Province, reports to

Governor-General Taft about problems of law and order.[80]

1904

Kiram-Bates Treaty is abrogated[81]“because of the Sultan’s

inability to maintain public order and the annual payment provided for therein

were discontinued.

In conferences held with American officials, the Sultan

repeatedly claimed that he had on no occassion abdicated or renounced his

sovereignty. He continued to excercise his judicial prerogatives in the trial

of both criminal and civil (cases) among the Moros in the Sulu archipelago.

March 21, 1904

The Philippine Commission concurs with Gen. Leonard Wood’s

decision to abrogate the Kiram-Bates Treaty.

November 12, 1904

Act No. 1259 of the Philippine Commission.

The law provided for annual payments to the Sultan of Sulu

and his advisors in view of the abrogation of the Bates-Kiram Treaty

April 12, 1905

Act No. 1320 of the Philippine Commission.

The law added Hadji Tahil and Hadji Sali to the recipients

of the annual payments.

November 19, 1906

Note of the U.S. Department of State to the British Embassy

in Washington, D.C.

…the US Department of State stated that Sabah was not an

Imperial possession of the British Crown, that the British North Borneo Company

which had leased Sabah from the Sultan of Sulu, did not have a national status,

and that the company did not have an administration with the standing of a

government[82]

March 11, 1915

American Authorities call the Sultan of Sulu to Zamboanga,

“and directed (him) to bring with him his advisors and persons of his

confidence.”[83]

March 13 – 22, 1915

Conferences with the Sultan of Sulu (in which “no nominal

recognition was given to the Sultan’s cabinet or council”)[84]

March 22, 1915

Carpenter Agreement

Governor of Mindanao and Sulu Frank W. Carpenter signs an

agreement with the Sultan of Sulu which relinquishes the Sultan’s, and his

heirs’, right to temporal sovereignty, tax collection, and arbitration laws. In

exchange, the Sultan gets an allowance, a piece of land and recognition as

religious leader.[85]

From Francis Burton Harrison’s recommendation on the

Carpenter Agreement in 1946:

The treaty “deprived the Sultan of his temporal sovereignty

in the Philippine Archipelago, but did not intrench upon the Sultan’s claims of

Sovereignty over the British North Borneo lands.”

On the Sultanate of Sulu: “The Sultanate of Sulu cannot be

abolished, save by direct action or neglect of the Moros themselves.”[86]

May 4, 1915

Frank W. Carpenter, writing to the Bureau of Non-Christian

Tribes, on the Temporal Sovereignty and Ecclesiastical Authority of the

Sultanate of Sulu:

It is necessary, however, that there be clearly of official

record the fact that the termination of the temporal sovereignty of the

Sultanate of Sulu within the American territory is understood to be wholly

without prejudice or effect as to the temporal sovereignty and ecclesiastical

authority of the Sultanate beyond the territorial jurisdiction of the United

States Government especially with reference to that portion of the island of

Borneo which as a dependency of the Sultanate of Sulu is understood to be held

under lease by the chartered company which is known as the British North Borneo

Government…[87]

President Diosdado Macapagal wrote a letter to Sen. Leticia

Ramos-Shahani dated May 1, 1989 and referred to this letter but set its date at

May 4, 1920.[88]

British North Borneo Company attempts to have Sultan Jamalul

Kiram to take up residence in Sandakan to acquire a good title to the ownership

of the territories.

A palace was offered in Sandakan to place the Sultan of Sulu

under their protection. On two occasions, Gov. Carpenter had to send the Chief

of Police of Jolo to bring the Sultan back from attempting to go to Sandakan.[90]

May 23,1917

Bureau of Insular Affairs endorses to the War Department, a

memo from British Ambassador dated May 17, 1917 asking for a copy of March 22,

1915 Carpenter Agreement[91]

May 16, 1917

Act No. 2722

Authorizing the Governor-General to reserve Public Lands not

to exceed 4096 Hectares for the Sultan of Sulu and his direct heirs, and

granting “the usufruct thereof to the said Sultan and his heirs.”

October 29, 1919

The Anti-Slavery and Aborigines Protection Society sends

correspondence to the Colonial Office to call attention to the alleged

ill-treatment of natives in North Borneo and presses for inquiry; submits

statements of evidence given to the Society by Mr. R. B. Turner, Mr. de la

Mothe, and Dr. Williams.[92]

November 8, 1919

Colonial Office reply to Anti-Slavery and Aborigines

Protection Society states that with regards to the first subject of complaint

there is no need for further investigation. The British North Borneo Co. are

being communicated with to a view of an inquiry into the other allegations.

[93]

March 5, 1920

The Anti-Slavery and Aborigines Protection Society to the

Colonial Office expresses doubt that any advantage will accrue from an inquiry

by the President of the British North Borneo Company and requests to discuss

the charges personally with officials of the Company who have experience of

present conditions[94]

April 8, 1920

The Colonial Office to Anti-Slavery and Aborigines

Protection Society acknowledges receipt of correspondence dated March 5, 1920

and states the evidence adduced would not justify the Secretary of State in

interfering in the administration of North Borneo[95]

July 16, 1920

The British North Borneo Co. to Colonial Office enclosed

memorandum by the President of the Company showing the result of his inquiries

into the allegations made by the Anti-Slavery and Aborigines Protection

Society; trusts the Secretary of State will endorse view of the Court of

Directors that the result is to justify the administration of the Company and

to exonerate them from charges brought against them.[96]

July 30, 1920

Dayang Dayang Hadji Piandao as Special Agent of the

Philippine Government ratifies her oath of loyalty and submission to the

Philippines.[97]

August 24, 1920

British Colonial Office, to the Anti-Slavery and Aborigines

Protection Society states that, after perusing the report by the British North

Borneo Company, Lord Milner is of opinion that the charges made by the Society

have been satisfactorily met and he therefore proposes to take no further

action[98]

February 15, 1921

Senator Teopisto Guingona writes the Governor-General of the

Philippines requesting for a copy of the 1878 treaty between the Sultan of Sulu

and Alfred Dent and Overbeck.

The letter states that the current Sultan has lost his copy

in “one of trips”.[99]

February 28, 1921

The Office of the Governor-General of the Philippines

endorses Senator Guingona’s request to the Chief of the Bureau of Insular

Affairs of the United States War Department.[100]

April 14, 1921

The United States Secretary of War endorses the letter of

Senator Guingona to the Secretary of State for proper action.[101]

April 22, 1921

Deputy Secretary of State acknowledges the receipt of the

letter of request of the Secretary of War.[102]

May 18, 1923

Act No. 2722 amended by Act No. 3118.

Authorizing the Governor-General to grant the land to the

Sultans heirs.

June 11, 1926

Bacon Bill

Rep. Bacon files bill to separate Mindanao from the

Philippines. [103]

January 12, 1928

Act No. 3118 amended by Act No. 3430.

Allowed the grant of land situated in Basilan and adjacent

islands.

January 2, 1930

The Boundaries Treaty of 1930

Clarifies which islands in the region belong to U.S. and

which belong to the State of North Borneo; delimits the boundary between the Philippine Archipelago

(under U.S. sovereignty) and the State of North Borneo (under British

protection) [104]

1931-1934

Jamalul Kiram is appointed Senator of the 12th Senatorial

District.

July 4, 1931

The Sphere of London publishes Sultan Jamalul Kiram’s

narration on the loss of his Treaty with the British North Borneo Company dated

January 22, 1878, during his visit to Singapore (as stated in the Sultan’s

letter addressed to Aleko E. Lilius, journalist for The Sphere).[105]

1933

Sultan Ombra, then only a datu and scion of royalty in

Tawi-tawi married Dayang Dayang Hadji Piandao.[106]

November 15, 1935

Philippine Commonwealth is inaugurated.

1935 Constitution

Article I, National Territory:

The Philippines comprises all the territory ceded to the

United States by the Treaty of Paris concluded between the United States and

Spain on the tenth day of December, eighteen hundred and ninety-eight, the

limits which are set forth in Article III of said treaty, together with all the

islands embraced in the treaty concluded at Washington between the United

States and Spain on the seventh day of November, nineteen hundred, and the

treaty concluded between the United States and Great Britain on the second day

of January, nineteen hundred and thirty, and all territory over which the

present Government of the Philippine Islands exercises jurisdiction.

June 11, 1936

Sultan of Sulu (Jamalul Kiram) dies and the question of the

perpetuation of the Sultanate is raised. Sultan Muwallil Wasit succeeds his

brother but dies before he was crowned.[107]

Brother is the claimant though his niece Dayang-Dayang,

married to Datu Ombra, wishes to be Sultana. Quezon considers her to be the

ablest of the Moros but Mohameddan law does not permit a woman to be Sultan.

Harrison points out large portion of political sovereignty already surrendered

to Wood in 1903 and Carpenter in 1915. Quezon to recognize Sultan only as the

religious head. British North Borneo Company expressed interest because of the

stipend paid by the Company to the Sultan.[108]

November 21, 1936

Sultan Muwallil Wasit dies.

January 29, 1937

Datu Ombra Amilbangsa is proclaimed Sultan of Sulu.

He is the husband of Dayang Dayang Hadji Piandao. His title

becomes Sultan Mohammed Amirul Ombra Amilbangsa. His Crown Prince is Esmail

Kiram, having given up his own present pretentions to the Sultanate[109]

About the same time, Datu Tambuyong is proclaimed and

crowned Sultan.

His title becomes Sultan Jainal Aberin. He chose Datu

Buyungan, his brother and at the time, the husband of Tarhata Kiram, as Crown

Prince.[110]

1937-1950

While Esmail Kiram I did not assume the throne, Dayang

Dayang makes her husband, Datu Ombra Amilbangsa, Sultan. Datu Tambuyong is also

crowned Sultan but by opposing Moro leaders.

Datu Ombra is named Sultan Amirul Ombra Amilbangsa; Datu

Tambuyong is crowned Sultan Jainal Aberin. The two claimed the sultanate from

1937-1950.[111]

May 9, 1937

Through the efforts of Dayang Dayang, the British resume

payment of lease. [112]

September 20, 1937

Memorandum on Administration of Affairs in Mindanao of

President Quezon to Secretary Quirino.

Titles of Datus and Sultans are recognized but have no

Official Rights and Powers[113]

October 2, 1937

Representative of Sulu Datu Amilbangsa writes to President

Quezon.

Datu Amilbangsa claims that the policy as released covering

this subject was most unnecessary, as the non-recognition has already taken

effect since the abrogation of the Bates Treaty and the implantation of the

Civil Government in the regions referred to. [114]

October 8, 1937

Three-point policy for Mindanao and Sulu letter from the

Executive Secretary Jorge Vargas to the Representative of Sulu Datu Amilbangsa.

Jorge Vargas communicates President Manuel L. Quezon’s

policy to recognize the titles of Datus and Sultans but no official rights and

powers.[115]

October 1939

Dayang Dayang Hadji Piandao and the eight heirs of the late

Sultan of Sulu request Calixto de Leon as their legal counsel to go to Borneo

to bring back the decision from the British Court.[116]

December 18, 1939

High Court of the State of North Borneo hands down decision

in Civil Suit No. 169/39. In it, North Borneo Chief Justice C.F.C. Mackaskie

stated that the heirs of the Sultan were legally entitled the payment for North

Borneo, which the decision calls “cession payment” on the basis of an English

translation by Maxwell and Gibson.

In the same decision, Mackaskie renders an obiter dictum

opinion or side note, that the Philippine Government is the

successor-in-sovereignty to the Sultanate of Sulu.

This obiter dictum however, does not establish a legal

precedent, and was furthermore based on a report from the British Consul in

Manila, claiming that the Commonwealth Government had abolished the Sultanate

of Sulu

Note: The first to challenge the Maxwell & Gibson

translation used by the High Court of the State of North Borneo is Francis

Burton Harrison, who pointed out in 1946-47 that Chief Justice Mackaskie used

the British translation of the North Borneo agree which stated that the land

was ceded; he submits a different translation by Prof. Conklin, obtained

through H. Otley Beyer. [117]

December 20, 1939

Account of the Cession Money now due and payable to the

heirs of the late Sultan of Sulu signed by W.A. C. Smelt, Treasurer, in Sandakan.[118]

March 8, 1940

Dayang Dayang Hadji Piandao relinquishes absolutely and

forever all her existing and future claims against the Government of the

Philippines, except for claims of ownership to certain islands located between

Borneo and Sulu[119]

April 4, 1940

Dayang Dayang renounces her claim against the Philippine

Government over the Sultanate of Sulu.[120]

May 6, 1940

British Consul-General S. Wyatt-Smith sends a reply to the

Office of the United States High Commissioner, relative to the judgment in the

suit filed by Dayang Dayang Hadji Piandao Kiram and eight others claiming to be

the heirs of the late Sultan Jamalul Kiram versus the Government of North

Borneo. The letter encloses a copy of the judgment and a statement of account

showing the distribution of the payment to the heirs.[121]

May 7, 1940

Secretary to the President Jorge B. Vargas sends a letter to

United States High Commissioner enclosing a copy of the following documents:

Document dated July 30, 1920 relative to Dayang Dayang Hadji

Piandao’s employment as Special Agent of the Philippine Government;

Copy of the declaration of Dayang Dayang Hadji Piandao dated

March 8, 1940, relinquishing absolutely and forever all her existing and future

claims against the Government of the Philippines.[122]

May 9, 1940

The Office of the United States High Commissioner sends

letter to the U.S. Division of Territories and Island Possessions enclosing the

following:

Letter from Jorge Vargas to the Office of the U.S. High

Commissioner dated May 7, 1940;

Copy of the decision of the High Court of the State of North

Borneo with letter of British Consulate General dated May 6, 1940[123]

September 6, 1940

United States High Commissioner Francis B. Syre, after a

trip to Mindanao and Sulu, said that the he was going to look into the matter

of the lease and that “the matter is very much alive”.[124]

1942-1945

World War II

1943: Quezon's Proposed Union with Indonesia

1943: Quezon’s Proposed Union of the Philippines and

Indonesia (marked in blue on map)

1946

Malayan Union Created

Provinces included:

Federated Malayan States

Unfederated Malayan States (Johor, Kedah, Kalantan, Perils,

Terengganu)

Malacca

Penang[125]

June 18, 1946

American attorneys representing the heirs of the Sultan of

Sulu denounce British action of annexation of North Borneo calling it an

unauthorized act of agression.[126]

June 26, 1946

British North Borneo Company cedes colony to the Crown.

Thus, annexing North Borneo to the British Empire.[127]

July 4, 1946

Inauguration of the Third Philippine Republic.

July 16, 1946

British Government annexed the territory of North Borneo as

a Crown Colony[128]

September 19, 1946

Vice President and Secretary of Foreign Affairs Elpidio

Quirino requests from the Embassy of the Philippines in Washington the

following documents:

Photostatic copy of the 1878 lease of Borneo lands of Sultan

of Sulu;

Documents containing records in any way related to the

rights of the former Sultan of Sulu over certain territories in northern

Borneo;

Copy of a book entitled, History of Sulu and Acquisition of

Borneo by Carl M. Moore.[129]

September 26, 1946

Presidential Adviser on Foreign Affairs, Francis Burton

Harrison, writes a recommendation to the Department of Foreign Affairs that the

Philippines should launch a protest against Britain’s annexation.

Francis Burton Harrison was former American Governor-General

of the Philippines. He became a Filipino Citizen in 1936 and was an advisor on

Foreign Affairs to President Manuel Roxas.[130]

October 10, 1946

Narciso Ramos reports to Secretary of Foreign Affairs

Elpidio Quirino on the status of his search for the book History of Sulu and

Acquisitions of Borneo by Carl M. Moore and photostatic copy of the Deed of

Lease (in Arabic characters) executed in 1878 by the Sultan of Sulu over

certain properties located in northern Borneo.[131]

November 25, 1946

“Sarawak Case to be Placed before U.N.”

The case of the annexation of North Borneo was placed in the

agenda of the United Nations by a group of British citizens who declined to be

a part of the British Empire.[132]

December 8, 1946

Francis Burton Harrison writes a second memorandum on the

government of the Sultanate of Sulu. See H. Otley Beyer Brief memorandum on the

government of the Sultanate of Sulu and powers of the Sultan during the 19th

century.

In the memorandum, Francis Burton Harrison mentions that he

asked a Professor Otley Beyer to translate the original lease of North Borneo.

Beyer translates it as the land being Leased and not as ceded.[133]

December 11, 1946

Memorandum of Eduardo Quintero to a Dr. Gamboa from

Washington D.C.

In the memorandum Quintero points out that there are three

existing translations of the lease. The first is the Maxwell & Gibson

Translation used in the Macaskie decision. The Second in the translation of

Prof. Conklin stating that the contract was a lease. The third translation by

Dr. Saleeby in the book “History of Sulu”. Quintero concludes that the contract entered into by Dent and Overbeck

was a lease and not a cession because it was similarly worded with the contract

entered into by Claude Lee Moses and Joseph W. Torrey.[134]

December 13, 1946

Ambassador Joaquin Elizalde responds to Vice President

Quirino’s request dated September 19, 1946 by enclosing the requested documents

pertinent to the North Borneo case.[135]

February 27, 1947

Francis Burton Harrison: Recommendation to Secretary of

Foreign Affairs and Vice President Elpidio Quirino:

The action of the British Government in announcing on the

16th of July (1946), just 12 days after the inauguration of the Republic of the

Philippines, a step taken by the British Government unilaterally, and without

any special notice to the Sultanate of Sulu, nor consideration of their legal

rights, was an act of political aggression, which should be promptly repudiated

by the Government of the Republic of the Philippines. The proposal to lay this

case before the United Nations should bring the whole matter before the bar of

world opinion.[137]

October 9, 1947

Washington, D.C.: Memorandum signed by J.P. Melencio.

Melencio recommends that the recommendations of the Francis

Burton Harrison be followed. He further recommends that the Philippine government

talk to the British government as to the basis of their annexation of North

Borneo. Once all the legal documents are compiled, Melencio recommends that the

matter be brought up to the International Court of Justice.[138]

January 31, 1948

The Federation of Malaya was created.

Malay States became British Protectorates.

Malacca and Penang remained as British Colonies.[139]

January 6 – May 11, 1950

A confidential memorandum was sent to Carlos P. Romulo via

acting Secretary of Foreign Affairs Felino Neri.

An attorney Calixto de Leon, asked for certification in

connection with a power of attorney that heirs request the money due from the

British goverment.

De Leon further revealed that Judge Antonio Quirino, brother

of President Elpidio Quirino, holds a power of attorney from the heirs to

transfer or sell their right to North Borneo and is about to consummate and

agreement with a third party.

1950-1974

Sultan Esmail Kiram assumes the throne until his death in

1974.

April 28, 1950

House of Representatives approved Concurrent Resolution No.

42 expressing the

sense of the Congress of the Philippines that North Borneo

belongs to the heirs of the Sultan of Sulu and the ultimate sovereignty of the

Republic of the Philippines and authorizing the President (Elpidio Quirino) to

conduct negotiations for the restoration of such ownership and sovereign

jurisdiction over said territory.

The Senate did not approve the Resolution.

Reps. Macapagal (Pampanga), Rasul (Mindanao and Sulu),

Escarreal (Samar), Cases (La Union), Tizon (Samar), Tolentino (Manila), and

Lacson (Manila) author the Resolution. [140]

September 4, 1950

Philippines advised British Government that a dispute

regarding ownership and sovereignty over North Borneo existed between the two

countries.[141]

September 11, 1950

British Government in a formal diplomatic note to the

Department of Foreign Affairs states its position on the North Borneo Case.

The position is stated thus: British North Borneo is held by

the British Crown in full sovereignty ; it is not leased either from the said

private heirs (the heirs of the Sultan) or from any other party or parties

whomsoever; consequently, the annual sum of Malayan $5300 which have been paid

to those persons are not ‘rentals’ but disbursements of cession money which the

Government of North Borneo have freely undertaken to make[142]

November 27, 1951

Luis Sabater, Legislative Counsel and Chief of Legislative

Reference Service consults DFA Legal Adviser Atty. Eduardo Quintero on the

title and rights to North Borneo of the heirs of Sultan of Sulu in connection

with the proposed bill for the purchase by the Philippine Government of the

lands owned in British North Borneo by the aforementioned heirs of the Sultan

of Sulu (authored by Representative Leon Cabarroguis).[143]

December 11, 1951

Secretary of Foreign Affairs Carlos P. Romulo hands the

Quintero report and memorandum for President Quirino stating the recommendation

of the Department of Foreign Affairs regarding the North Borneo case:

Increased payment;

Claim of

sovereignty.[144]

DFA recommendations:

Increased payment: “prospects are very encouraging” to

revise payments;

Claim of sovereignty:

“prospects are not so bright” based on British government response and that

Philippines had never declared itself a successor-in-interest to the Sultanate

of Sulu, therefore, claim must be pursued through heirs of the Sultan.

February 1, 1952

Atty. Eduardo Quintero informs Secretary of Foreign Affairs

Carlos P. Romulo through a memorandum that according to the report of Judge

Guingona, the territorial possessions of the Sultan of Sulu in North Borneo

contains an area of 31,000 square miles, with 300,000 inhabitants and that the British

Government can realize 9 million dollars annually from forest products

alone.[145]

October 16, 1952

V. Diamonon sends a letter to Atty. Eduardo Quintero stating

the request of Congressman Escareal for a copy of the North Borneo

documents.[146]

November 3, 1952

Eduardo Quintero sends Memorandum for Mr. Holigores

forwarding confidential documents on the Sultan of Sulu Case.[147]

August 30, 1955

Vice President Carlos P. Garcia and the British Ambassador

to Manila signed an agreement that provided for the employment and settlement

of 5,000 skilled and unskilled Filipino agriculturists and miners in North

Borneo.

Agreement not implemented as North Borneo employers feared

multiple suits arising from claims of Filipino laborers: they had found a

sizable number of Indonesians willing to work on a temporary basis.[148]

January 1957

Governor of North Borneo visits Manila to implement the 1955

labor treaty.

500-man delegation of Filipino Muslims present resolution to

President Ramon Magsaysay calling for direct negotiations with the British to

return North Borneo to the Philippines. Magsaysay did not act on the

resolution.

British response: United Kingdom High Commissioner for

Southeast Asia said it would not take seriously the demands of Moros in the

Philippines for certain areas of North Borneo.[149]

July 31, 1957

The Federation of Malaya Act was signed.

The Federation of Malaya was established as a sovereign

country within the British Commonwealth.[150]

November 25, 1957

Muhammad Esmail Kiram, Sultan of Sulu, issued a proclamation

declaring the termination of the Overbeck and Dent lease, effective January 22,

1958.

All lands were to be deemed restituted henceforth to the

Sultanate of Sulu.[151]

1957

A syndicate headed by Nicasio Osmeña acting as attorney-in-fact

for the heirs, attempted without success to negotiate with the British Foreign

Office for a lump sum payment of $15 million in full settlement of the lease

agreement.[152]

August 31, 1957

Thank you for your so cool post. Please share with us more good post.

ReplyDeleteBuy Flat Earth Map