INTRODUCTION

“Thus

has Marudu ceased to exist;

and Seriff Houseman’s power received a fall from which it will never recover”,

James Brooke wrote in his diary (1) on 20 August 1845 after a

successful campaign against Syarif Osman of Marudu, (2) which had its eventual tragic

climax in the destruction of Marudu by the British Navy.

Brooke had managed to convince Vice Admiral Thomas Cochrane to proceed with a great fleet against Marudu. The accusation of piracy, which Brooke used intentionally against Syarif Osman, served Brooke as a pretext for the attack. However, on closer examination, this accusation turns out to be false. Nevertheless, Cochrane and other commanders of the British ships, as well as colonial officials, relied on Brooke’s details because, in their opinion, he had insight into the situation in Borneo and because he presented authorities in Singapore, India and London with documents containing allegedly incriminatory evidence against Syarif Osman.

Brooke had managed to convince Vice Admiral Thomas Cochrane to proceed with a great fleet against Marudu. The accusation of piracy, which Brooke used intentionally against Syarif Osman, served Brooke as a pretext for the attack. However, on closer examination, this accusation turns out to be false. Nevertheless, Cochrane and other commanders of the British ships, as well as colonial officials, relied on Brooke’s details because, in their opinion, he had insight into the situation in Borneo and because he presented authorities in Singapore, India and London with documents containing allegedly incriminatory evidence against Syarif Osman.

|

| James Brooke |

Brooke’s actions have had lasting

influences on historiography. The British commanders on site, Keppel and Mundy,

cited long passages from Brooke’s diaries (the Journals). Furthermore, in

direct contact with Brooke were John Templer, Spenser St. John, and Brooke’s

nephew, Charles Brooke, and in their books they repeated — like the British

commanders — Brooke’s portrayal of Marudu as a pirate’s nest. Horace St. John,

Gertrude Jacob, Sabine Baring-Gould and Charles Bampfylde, who wrote

biographies of Brooke, relied on the same information. As a result, the misrepresentation

of Marudu found its way into the twentieth century; for example, into the works

of Owen Rutter, Emily Hahn and Robert Payne. In books concerning the history of

Sabah and Sarawak it was customary to portray Syarif Osman as a pirate; for

example:

“A famous pirate leader of Borneo at that time was Sherif Osman”

(Mullen 1961: 50–51);

“One of the most famous pirate strongholds in the history of piracy in the East Indies was at Marudu … and their leader was the widely-known Serip Usman” (Whelan 1968: 1).

“One of the most famous pirate strongholds in the history of piracy in the East Indies was at Marudu … and their leader was the widely-known Serip Usman” (Whelan 1968: 1).

It was also included in more

general works that do not necessarily have historical content; for example, in

the travel reports of Cyril Alliston (1961), who portrayed Marudu as one of the

largest pirate places. David Leake (1989) called Syarif Osman a ‘pirate leader’. Such representation

can be found even in some more recent books which touch upon the topic. (3)

However, since the 1960s a more

differentiated discussion has appeared in the academic literature dealing with

the colonial history of northwest Borneo. In particular, Ingleson, Bassett and

Warren come to different conclusions from those previous authors who reflected

the events only from Brooke’s perspective. All three authors stressed that in

fact Brooke was the initiator in the destruction of Marudu because he had

defamed Syarif Osman as a pirate.

Malaysian authors considered Syarif Osman as a hero who was brought down by the British:

“Matilah seorang pahlawan keturunan darah Raja akibat pengkhianatan dan hasutan Inggeris” (Buyong 1981: 15).

Malaysian authors considered Syarif Osman as a hero who was brought down by the British:

“Matilah seorang pahlawan keturunan darah Raja akibat pengkhianatan dan hasutan Inggeris” (Buyong 1981: 15).

In the book Commemorative History of

Sabah 1881–1981, edited by Anwar Sullivan and Cecilia Leong, which was

published by the Sabah State Government on the occasion of the 100th

anniversary of Sabah, Marudu was described as an independent chiefdom whose

interference in the politics of Brunei led to Vice Admiral Cochrane declaring

Marudu as a pirate stronghold and destroying it. Nevertheless, nineteenth century

colonial officials were already in doubt as to the representation of Osman as a

pirate.

Thus Bulwer wrote:

“Yet it is

very doubtful if he [Osman] was guilty of the charge brought against him by the

Brunei Government. He was of Arab descent and a man of character and energy,

and he was acquiring a power and influence which were disagreeable to the

Pangerans of Brunei.” (4)

Even Captain Belcher, who sailed

with Brooke to Brunei in 1844 and who in his letters to the Admiralty supported

Brooke’s defamation of Syarif Osman, came to a different assessment in his book

after having learnt in Manila of the real behaviour and motivation of Syarif

Osman:

“At Maludu Bay, in particular,

the destruction of Seriff Housman has deprived the people of that region, of

the only energetic ruler who could have afforded protection to European

traders” (Belcher 1848: II, 124).

Before Syarif Osman was defamed by Brooke

he was recognised as ‘Rajah of Maloodoo’

by Governor Butterworth of Singapore (Belcher 1848: I, 170), and even Pascoe,

who took part in the Battle of Marudu as an officer, described him as Rajah

(Pascoe 1886:49).

It is difficult to find reliable

contemporary information about Syarif Osman and Marudu. Generally history is

written by the winners — and this certainly applies to Marudu. There are few

neutral statements from that period. Those statements which have emerged in

connection with Brooke’s campaign are biased. One can try to reinterpret them;

for example, from Brooke’s statement that Syarif Osman was a known pirate

leader one can at least deduce that he was a prominent leader.

The source literature on Syarif

Osman consists of official archival letters (the correspondence of the officers

involved in Southeast Asia with the ministries — the Foreign and Colonial

Offices and the Admiralty — in London, as well as interministerial exchanges),

periodicals (Journal of the Indian Archipelago, Singapore Free Press, Straits

Times, Illustrated London News and British North Borneo Herald), private

correspondence (letters between persons involved are also to be found in

archives in London as well as in the Philippine National Archives in Manila;

the correspondence and journals by James Brooke are to be found in the books of

Keppel (1846), Mundy (1848) and Templer (1853)), and travel literature written

by persons involved such as Keppel (1846, 1853), Belcher (1848), Mundy (1848),

Marryat (1848), Cree (Levien 1981) and S. St. John (1862).

If these written sources

are evaluated impartially, the relevant oral traditions reviewed carefully and the

historical situation of northern Borneo before and after Syarif Osman (as well

as the position of his descendants) fully considered, then the importance of

Marudu at the time of Syarif Osman can be ascertained, even though perhaps not

completely understood. This article, based on my extensive study, (5) represents an

attempt to do so.

MARUDU

The

Claims of Brunei and Sulu to Marudu.

The sixty-kilometre-long Bay of Marudu is

located between the Sulu Sea and the South China Sea. The land adjacent to the

large bay is crossed by many rivers where settlements were established. The bay

and the nearby islands formed the core area of Syarif Osman’s territory. To the

south, mountains framed the bay. (6) The name Marudu already appeared on very

rudimentary fifteenth-century Portuguese maps, (7)

on which not many local names were shown.

Marudu lay midway between the

spheres of influence of Brunei to the west and Sulu to the east. Both had laid

claim to Marudu throughout history because they wanted to control its many

economic resources. (8) Though Borneo’s soil may not have been as fertile

as that of the Malay Peninsula, Marudu is represented in the early nineteenth century

as the most fertile region in northern Borneo.(9)

Marudu had been conquered by Sultan

Bolkiah of Brunei (reigned 1485–1524) who extended his power over most of

Borneo as well as Sulu and, most likely, Luzon. (10) Brunei became the most powerful

sultanate of that region. Later, Marudu became part of the inheritance of

family members of Sultan Hassan of Brunei. In the eighteenth century there were

internal problems in Brunei which led to a civil war, after which the areas

north of Kimanis were ceded by the Sultan of Brunei to Sulu in gratitude for its

successful intervention in the civil war. Sulu gained importance in the

eighteenth century through its extremely lucrative middleman role with the

British/Indian– Chinese tea trade.

Thus with Brunei’s civil war the

situation regarding suzerainty in northern Borneo had changed. In 1761 Alexander

Dalrymple had to deal with Sulu, not with Brunei, when he planned to obtain the

island of Balambangan, where he wanted to establish a British trading post. He

listed the Bornean coastal regions that belonged to Sulu as Tirun, Magindora,

Marudu, and Kinabalu/Papar. (11) Brunei still laid claim to them and

quarrelled with Sulu over the issue. In the 1780s Iranun people settled on the

coast between Tempasuk and Marudu and established local markets, which quickly

became trading centres. The stronger the Iranun were, the weaker was Brunei’s

influence in the more northern lands. Brunei’s de facto influence ended where

the Iranun districts began. Marudu formed at that time a kind of border

territory between the spheres of influence of Sulu and Brunei.This is supported

by the observation of Hunt (Keppel 1846: I, Appendix II: lx, lxi) that in the

early nineteenth century the Bay of Marudu was divided into two spheres of

influence: the river district Songy Bessar (Sungei Besar) was ruled by Syarif

Mahomed and sent its products to Sulu, while Benkaka (Bengkoka) was ruled by an

orang kaya who traded with Brunei. However, according to Dalrymple, the leaders

of northern Borneo were virtually independent from the sultanates of Brunei and

Sulu because of the eighteenth-century conflict between the sultanates. (12)

Both sultanates were weakened

further due to succession disputes in the 1820s. Moreover, Sulu was weakened by

the centuries-long Moro Wars with the Spanish, (13) and a war of succession after 1823

contributed to the waning of Sulu’s de facto control, especially in the

northern Borneo territories. Likewise, Brunei had to struggle in the 1820s with

internal succession problems, and had to deal with the British and Brooke less

than twenty years later. So both sultanates had lost even more power after 1820,

paving the way for the rise of a new government structure which was able to

fill the power vacuum that had emerged in northern Borneo through the elimination

of de facto control by the two sultanates.

Marudu

as an Independent Polity

At least since the 1820s, a

tri-partition of spheres of influence could be observed in Sabah: Brunei, Sulu,

and de facto independent territories between the two sultanates. (14) These independent polities were designated as

no-man’s-land (Short 1969: 136) or as pirate states (Wright 1979–1980: 209).

Since the designating of Marudu as a pirate state is an invention of James

Brooke, the label ‘state’ still needs to be considered. According to political

theory studies the de facto control is crucial:

“A state will therefore be considered as independent if its

independence is de facto” (Claessen & Skalnik 1978: 19).

Syarif Osman cannot be represented

as a subject of Brunei and Sulu since the two sultanates no longer ruled over

the north of Borneo, which had become de facto independent. Singh lists Marudu

as the main example of the independent chiefdoms and points to their autonomous

status:

“They were a law unto themselves

and recognised no superior suzerain” (Sullivan & Leong 1981: 94).

Syarif Osman was of course

independent, but to mark him only as a chief does not accord with the political

structure that he had created in Marudu. According to writings on types of

government, the difference between a chiefdom and a kingdom consists of the

ability of the king to delegate his power, which is then exercised on his behalf.

(15) Syarif Osman delegated his power to

other syarif who resided on the many rivers of the bay and who were subordinate

to him. If Syarif Osman had restricted himself to only one river district, then

one could describe him as a chief. However, since he had united both sides of

the large bay and other areas and islands were also under his government, he

can be described as an independent ruler who was ambitious to build up his own

polity.

The creation of a polity in Marudu

was not an automatic or natural process, as a comparison between Marudu and the

island of Cagayan in the Sulu Sea shows. On Cagayan also, Sulu’s control was no

longer effective in the nineteenth century. Here, however, no one took

advantage of the opportunity to establish himself as a ruler. As in Marudu,

there was a foreign coastal population with syarif and datu who, together with

the traditional aristocratic leaders of the indigenous people, occupied the

position of heads. They divided the government into four main districts which

Casiño (1976: 29) describes as semi-independent although the island was still

officially under the control of Sulu. In this context, he points to the problem

that there was no resident authority in Cagayan who could unite these districts

into a single coordinated political unit.

Therefore, no leader in Cagayan

succeeded in doing what Syarif Osman achieved in Marudu by virtue of his

charismatic personality. The more successful a leader was — whether a sultan,

datu or syarif — the more his political structure stood out from the mass of

petty principalities. Syarif Osman was able to use the power vacuum to create

Marudu as an independent and organised political entity and to break loose from

Sulu’s weakening control.

Both before and after Syarif Osman,

no one managed to forge Marudu Bay into a single unit. Although Syarif Osman

built a dynasty, it was weakened by the defeat in 1845, so that it could not

continue to hold the polity together. Three years after the Battle of Marudu, a

son of Syarif Osman complained to the Briton Keppel about the unstable

situation in Marudu: ...

he [i.e. the son of Syarif Osman]

and the chiefs with him admitted that nothing could be worse than the

unprotected state and want of government, under which they lived; that each

petty chief quarrelled with and attacked his weaker neighbours, while they, in

turn, lived in constant dread of an attack from the more formidable Bajow, or

Soloo pirates (Keppel 1853: I, 45).

Members of Syarif Osman’s family

ruled even after the defeat in areas of Marudu, but none of them managed to

unite the communities around the bay. His son Syarif Hassan resided in the south

of Marudu Bay but had conflicts with other leaders and was even expelled

temporarily.(16)

Another son, Syarif

Yassin, fought in the Battle of Marudu and fled temporarily to Sugut. (17)

He was perceived as Raja when residing in Benggaya in

1851, (18) and — as ‘Sheriff Yassin of Malludu’ —

even as principal chief of the Bay of Marudu in 1879 by the British.(19) Syarif Yassin and, after Yassin’s

death, his son Syarif Hussin resided on the eastern side of Marudu Bay, and

Yassin’s sister Syarifa Loya was chief of Kalimo village on the Bongon River.

There were also other relatives not mentioned by name, such as the cousin who

resided in southern Palawan. Thus the claim of the family still existed, albeit

in competition with others such as Datu Badrudin and the family of Syarif Shee

who ruled the areas on the western side of the bay (which had previously paid

tribute to Syarif Osman). (20) In 1845 Syarif Shee’s family had

also fought under Syarif Osman and did not doubt his claim to leadership — as

Syarif Shee even told the British North Borneo administrator W.H. Treacher (CO

874/72, 8 May 1879).

So after 1845, the Bay of Marudu was

again divided into various spheres of influence which resembled not just a

disorganised, but already a lawless, state — as the British observed when

establishing the British North Borneo Company in the late 1870s:

“The

destruction of the region’s ‘only

energetic ruler’ … produced a descent into the near complete anarchy

Pretyman discovered in 1878” (Black 1968: 178). (21)

It was typical for Malay

thalassocratic (maritime) polities that when their organisation was broken,

they were stagnant or in decline. Marudu under Syarif Osman shows the characteristics

of a Malay thalassocracy. It had developed out of Sulu, as Sulu had itself

developed out of Brunei in the eighteenth century, and Brunei’s basic polities were

based on Johore Lama and Malacca. (22) They all had their precursors in

Srivijaya and were trade-oriented coastal states — that is, thalassocracies —

which had mainly in common the Malay language, similar characteristics of

political organisation and, most importantly, trade orientation.

The Malay-maritime coastal states

were created by a group of immigrants who settled on a particular coast and

then dominated the river mouths. (23) The previous resident population

became subordinated to the immigrants and, over time, also took on the values,

customs (24) and religion of the immigrants or

retreated into the interior, where possibly other groups also had to withdraw.

In northwestern Borneo the Malays occupied the coast but did not advance

inland. They settled near the river mouths and were therefore able to control

the trade which flowed upstream and downstream. The inland village communities

were considered a basic political unit,(25)

with several settlements

on a river forming a river district. Syarif Osman united many river districts under

his leadership.

According to Singh (1990: 237–239),

three different zones of economic use can be identified for Brunei and Sabah.

The first zone was the mountainous jungle areas, the primary source of jungle

products. This zone was inhabited by the Dusun/Murut.

After 1845 several

leaders of the Bay of Marudu admit that “that there were many tribes among the

mountains with whom they had little intercourse” (S. St. John 1862: I, 390).

Such statements confirm that the mountainous tribal population did not consider

themselves as subordinates of a particular coastal polity after the decline of

Marudu, whereas, prior to the Battle of Marudu, Syarif Osman seems to have

exercised control over the neighbouring interior tribes (Keppel 1846: II, 192).

The second zone was the coastal lowland zone, which extended about 20 to 40

miles inland, and where wet rice was grown.

The Dusun also lived there, but

this area was dominated by the later immigrants. This zone is considered by

Gullick (1969: 168) as a contact zone between foreigners (outside influence)

and natives (interior people) in Sabah. Third was the sea zone, which was used

mainly for fishing by immigrants from Sulu. In Marudu, the immigrant Bajau,

Iranun and Tausug were the coastal population and were also perceived as Malay

authorities (Belcher 1848: II, 120), while the Dusun (26) were the earlier inhabitants.

SYARIF

OSMAN

Syarif

Osman’s Claim to Leadership

Syarif Osman belonged to the Malay

immigrant society and was considered a foreigner. Because of his title Syarif, (27) he could easily find acceptance as a prestigious, idol-like

leader:

“sereibs or seriffs, descendants of the Prophet, have always been held in

high consideration. They are always addressed by the title of tuan-ku, or ‘your

highness’, and on state days and festivals occupy a position more eminent than

that of the highest hereditary nobles” (Low 1968 [1848]: 123).

Syarif

were thus equivalent to the members of royal lineages (28) and were able to marry into noble families. They also founded

sultanates, as in Sulu and Pontianak.(29) The origin myths of maritime

coastal states in Sabah as well as in the Philippines often go back to the

immigration of one or more syarif. (30) Thus syarif were predestined to

assume leadership, which was not limited to religion but affected the whole

society and politics.

A further strengthening of Syarif

Osman’s leadership resulted from his marriage alliances. One of his many wives

was the daughter of Sultan Pulalun of Sulu. This princess appears in the Sulu

genealogies, but not — as usual — by name. According to oral tradition she was

called Dayang Sahaya and was highly venerated in Marudu. Even Rutter (1991 [1930]:

205), who worked for the North Borneo Chartered Company from 1910 to 1915,

learned at Marudu that the princess was reputed to have had supernatural powers

and that her grave was very honoured.

Her brother was Raja Muda Datu Mohammed

Buyo, the successor to the throne and a friend of Syarif Osman. Spenser St.

John (1862: II, 207–8) reports how much Datu Buyo grieved for his dead sister

after the Battle of Marudu and was thereafter hostile to the British because

they were responsible for the defeat and death of his sister and brother-inlaw.

Also, Syarif Osman’s son Yassin and grandson Hussein married princesses of the

Sulu ruling family.

“Clearly, dynastic relations with older Muslim ruling houses of

neighbouring countries was an added item reinforcing legitimacy” (Majul

1977a: 653).

The marriage with Dayang Sahaya

meant that Syarif Osman and his direct descendants were able to protect their

primus inter pares claim against the other syarif and leaders in Marudu Bay.

The marriage was of mutual benefit for both Syarif Osman and the Sultan’s

family. Sulu was at the time under external political pressure, which is reflected

in the Treaty of 1836 with the Spanish. In Syarif Osman, Sulu won a reliable ally

and trade partner. Moreover, Syarif Osman married other daughters of Marudu Bay

leaders for political reasons. Thus these leaders felt bound to him because in

the traditions of northern Borneo and the southern Philippines the side into

which the women married was considered the stronger. (31)

In oral traditions the number of women who

married Syarif Osman is very high — forty or forty-four. The more women a

leader managed to acquire, the higher his prestige.(32) Moreover, the fecundity of the

leader was of great importance and was applied to the situation of the whole

country: the more fertile the leader, the more fertile the land. Syarif Osman

legitimised his position as the Raja of Marudu by his tactical polygamy, his

potency, his title, and his connection to an old Muslim dynasty.

The role of the raja is considered

prominent and central in the Malay world. Loyalty was an essential element

between ruler and subordinates who understood their position in relation to the

raja, (33) who was legitimised by a sacred

aura. (34) The person — not the office — was

important. The authority of the ruler was based on the willingness of his

supporters to remain loyal. He had to be able to bind the supporters to him. According

to Kiefer (1972: 93), the power of the leader was crucial to his supporters and

was largely derived from his wisdom and his justness, his prosperity, his

title, and the cannons that he possessed, as well as the number of loyal

followers.

Syarif

Osman as a Charismatic Leader

Even in the cultural sphere of Sulu,

to which Marudu belonged through their common waters, (35) a ruler not only obtained his

position through inheritance or because of his office, but also by virtue of

his own personality. This style of leadership may be designated as charismatic

authority. A charismatic leader is regarded as superhuman because of his

character, his strength and his ability to help his followers. (36) For the emergence of a charismatic leadership certain

conditions also had to be met; for example, the leader had to be a foreigner.

Syarif Osman was perceived as a foreigner simply because of his Arab title. (37) Furthermore, he also knew how to gather many

followers. He ruled by Islam and adat, and he was known for his strict style of

leadership, especially when seeing that the local customary law, the adat, was respected.

With Marudu expanding as a stable trading centre, more and more people came to

settle there because it offered prosperity and protection from pirates and from

the exactions of the colonial powers. Syarif Osman was described as strong, courageous,

ambitious, assertive and self-confident — so he must have seemed charismatic to

his supporters.

Syarif Osman also owned many

cannons. According to Casiño (1976: 29), Muslim coastal rulers had a monopoly

on these weapons, which symbolised wealth, power and the political office

itself. The British discovered eleven large guns in the fortress in Marudu,

together with numerous small brass cannons. In oral tradition the cannons

played an important role in the defeat. According to many accounts, the main

cannons were given particular names: Penamal, Mandi Dara(h), Bujang Si Dandam/Puasdandan,

Gentaralan. Appell, who recorded in the 1960s a legend of the Rungus Dusun

relating to the death of Syarif Osman, reported that there were three cannons

named Sorio, Puasdandan and Putut Karabau which had been endowed with supernatural

abilities by river spirits. It was Syarif Osman’s brother-in-law Pompugan who

fired the guns in the wrong order and was thus responsible for the defeat. (38) In this Rungus tradition, magic plays an important

role.

Supernatural qualities are essential

for a charismatic ruler. Syarif Osman was said to be generally in the

possession of supernatural properties (39) and invulnerable:

“as

he [Syarif Osman], being one of those whom they deem invulnerable, exposed

himself to every fire, and fought to the last” (S. St. John 1862: II,

207).

Spenser St. John (1862: II, 208) describes in this context the method of

creation of invulnerability (namely, through the “rubbing of their whole bodies

with some preparation of mercury”) which, according to him, differs

from the method in Sarawak. Magical powers were invested in Syarif Osman

himself or in persons near him, such as his wife Dayang Sahaya, or items such

as his guns.

In addition to his title and his

alliances through marriage, it was the charismatic qualities which legitimised

Syarif Osman as a leader and strengthened his claim to power. Typically, the

role of the raja in a Malay thalassocracy was so exalted that there were really

no — or only very rudimentary — other recognisable concrete administrative

structures.

“The Raja is not only the ‘key institution’ but the only institution,

and the role he plays in the lives of his subjects is as much moral and religious

as political” (Milner 1982: 113).

Syarif Osman had the typical key

position held by a raja: he was the political and religious leader, and

everything focused on him.

“The Malay conceptualisation of authority

was directly linked to the presence of a Raja; territory was unimportant, hence

the term kerajaan (the state of having a Raja), which is, more appropriately,

the Malay equivalent of the Western concept of a ‘kingdom’” (Khoo 1991:

20).

For Malay independent constructs the expression kerajaan can be considered

as an adequate designation, if there is a raja at the top. (40)

Marudu

as a Trade-oriented Thalassocracy

As a Malay thalassocracy, the Marudu

kerajaan was first of all trade-oriented. Trade can be understood as the

essential foundation of a Malay maritime coastal state.

It is described by Trocki

(1979: 52) as “the only source of political power that Malays had ever known”.

A successful thalassocracy was based on economic activities. The Malay maritime

states exerted primarily political influence if they were able to control the trade

with their peripheral areas. The trade was necessary for the ruler to gain

wealth, which in turn was important to guarantee a large following.

Therefore,

Milner (1982: 16, 17) states that “The kingdom was, in the final analysis, a

commercial venture, and Malay rulers were the greatest merchants in their

state.”

Syarif Osman concentrated on

acquiring the products that were important for trade with China, especially

birds’ nests. Similarly, marine products were obtained — fish, trepang (sea

cucumber or beche-de-mer), turtle eggs, pearls, mother-of-pearl, shells,

agar-agar and tortoise shell. Except for the first three, these products were mainly

used for trade. Trepang was an important domestic food item, but it was also an

important source of revenue in the markets of China and Sulu, as were pearls and

tortoise shell. The goods were stored in Marudu before sale. Other products in Marudu

were rattan, wax, wood, sweet-scented wood (kayu laka), and camphor. Tobacco

and rice were also cultivated and traded. The trade was important for the rise of

Marudu as a kerajaan. Syarif Osman knew how to organise and protect the trade. The

inland population did not come into contact with the merchants. According to

the structures of a Malay coastal state, it was the immigrant society who

organised trade and profited by it. By trading, Syarif Osman gained control

over the local population. He also needed to trade in order to pay his numerous

retinue, through which he became a recognised and respected leader.

In order to attract foreign traders

in the port, Syarif Osman not only built storehouses, warehouses and shipyards

in his harbour, but also took defence measures. His strong fortress, built to

secure trade, was two square miles in size, consisting of several forts and

batteries. The complex was protected on three sides by palisades. Protected within

the fortress stood — besides houses — warehouses and armouries, a village and

fields. (41) To be safe from pirate attacks, it

was situated a few miles upriver and secured by a wooden barrier with iron

chains which was stretched across the river and could not be destroyed by the

British forces. The fortress was one of the strongest in the whole region.

Furthermore, Syarif Osman had

entered into alliances with the Bajau and Iranun, so that they would no longer

be dangerous to him at sea. Likewise, Srivijaya had bound the Orang Laut

contractually. These nomadic sea-faring nations no longer committed piracy

against Srivijaya and Marudu, but rather protected the waters from pirate

attacks. According to Trocki (1979: 208), the rise of the Malay maritime

coastal states was dependent on the ability to control the sea off their

coasts. From the report of Earl, who travelled in Borneo in the early 1830s,

the conclusion can be drawn that in Marudu good, safe trading conditions had

been created:

The north-east end of Borneo has

not, I believe, been visited by a British vessel since the abandonment of

Balambangan, but, according to the accounts of the Bugis traders who sometimes

touch there, a very interesting change has lately taken place. They assert that

large bodies of Cochin Chinese are now established on the shores of Malludo Bay

and the adjacent parts; and as the Cochin Chinese are known to be settled in

considerable numbers on the neighbouring island of Palawan, there appears to be

no reason for doubting the correctness of their information (Earl 1971 [1837]:

322–323).

The settling of the Chinese in

Marudu suggests that Syarif Osman had already built a safe harbour with good

trading conditions. The goods which were handled in Marudu were indeed

primarily destined for the China market. Based on this reference and on oral

tradition (Gerlich 2003: 233) and, of course, on the development of the two neighbouring

sultanates, it can be assumed that Syarif Osman had established himself in

Marudu no later than the early 1830s.

Marudu’s

Spheres of Influence

Syarif Osman succeeded in increasing

the number of his followers by a functioning, organised trading system.This

enabled him to enter into more alliance partnerships and to bind more distant

river districts. He could demand tribute from communities that he in turn was

able to protect by his naval power. He had built a strong centre, which is

typical of a Malay thalassocracy, being defined by its centre and not by a delineated

territory.

Basically, there is an imbalance of power between the centre and

periphery areas. There are several terms to describe this phenomenon of Malay coastal

states which all emphasise the discrepancy between centre and periphery; for example,

the negara concept (Geertz 1980),(42)

the galactic polity

concept (Tambiah 1976), and the segmentary state model (Kiefer 1971). In the

segmentary state model, the authority outside the centre should not have been

exerted politically, but only ritually and symbolically, so these peripheral

districts could have been perceived as independent.

The same applies to

Wolters’ mandala concept (1982). According to him, the “mandala is an unstable ‘circle of kings’ in a territory without fixed

borders, in which each subjugated unit of the state remained a complete,

potentially independent polity with its own centre and court” (Christie

1985: 9).

These centre-periphery theories are

applicable to Marudu. As Sulu had become weaker it lost effective control over

peripheral areas, including Marudu. That was the prerequisite for the

independence of Marudu, which then itself formed a polity that resembled the

segmentary state model, similar to a mandala. Marudu had a strong centre and

effective control over neighbouring rivers. The farther away Marudu’s areas of

influence were, the weaker the influence and the more independent these areas

may have been; nevertheless, Marudu still had some influence there. Figure 1

illustrates Marudu’s spheres of influence. The dark grey field is the area in which

Syarif Osman’s influence was the strongest (the centre). The lighter the grey, the

weaker his influence.

The centre consisted of the fortress

lying on the Marudu River (later called the Langkon River). According to an

1851 list by Syarif Osman’s son Syarif Hassan, the people of the adjacent river

systems had paid tribute to his father, as had the people of the offshore

islands of Banggi and Balabac. Through this list, Syarif Hassan wanted to give

evidence to Spenser St. John (1862: I, 389 ff.) of the areas which had been

once subject to his father. Other leaders in the bay (Datu Bedrudin and Syarifs

Musahor, Abdullah and Houssein) confirmed his statements. Syarif Hassan’s list

cites the following locations (from north to south):

Udat, Milau, Lotong, Anduan, Metunggong,

Bira’an, Tigaman, Taminusan, Bintasan, Bingkungan, Panchur, Bungun and Tandek.

Therefore, Syarif Osman exerted influence from Kudat to Tandik. St. John also

mentioned the Bengkoka district, but the name does not appear directly in the

list.

However, the family of Syarif

Osman’s son Syarif Yassin built one of their main residences there. (43) According to S. St. John (1862: I, 391), Syarif Osman

had also tried to establish a settlement in Mobang (Melabong), which lies near

Bengkoka to the north. In the oral traditions, other places are mentioned as

being under Syarif Osman’s rule; for example, the village of Parapat near

Limau-Limawan, and the island of Tambun in front of the Bandau River mouth.

Kampar, where he lived and died, is mentioned as his home village.

The islands in the north of Marudu

Bay were also viewed by Syarif Osman as his direct sphere of influence. He had

recovered items from a wrecked and abandoned ship near Banggi, which confirms

that he regarded the area as his own. According to Belcher (1848: I, 194),

Syarif Osman had made an excursion with his ships from Banggi to Palawan. The

residents of Banggi paid tribute to the Malay authorities of Marudu Bay in

1846, even after the downfall of Syarif Osman (Belcher 1848: II, 120). The

Spanish clergyman Cuarteron, who was a resident of Labuan in 1857, reported that

fifteen years previously Syarif Osman had made a rather cruel expedition

against the people of Balabac as they had refused to pay tribute.(44) It is not surprising that Syarif

Osman wished to directly control the entrance to Marudu Bay.

In the medium grey region of Fig. 1

one can see the more remote river systems which also had to pay tribute but

could not be controlled as closely as the districts in the bay. Syarif Osman’s

influence extended east to approximately Labuk, and west of Marudu Bay to at

least Ambong, if not to the border of Brunei, which was then very probably Kimanis.

The island of Labuan, which is located opposite Brunei Bay and therefore still

further south than Kimanis, was also mentioned in contemporary sources in connection

with Syarif Osman. (45)

Three facts allow us to draw

conclusions about the reign of Syarif Osman over the Labuk/Sugut area. First,

his direct descendants Syarif Yassin (his son) and Syarif Hussin (his grandson)

also ruled there. Yassin fled to the area after the Battle of Marudu and

settled there. He was considered to be the supreme leader and had married a

daughter of a local chieftain named Datu Israel; this suggests he pursued a

marriage policy like his father. Second, the area was known as a particularly

good source of camphor, one of Syarif Osman’s main exports. (46) Third, this area lies in the direct eastern

neighbourhood of Marudu Bay and had already formed in Dalrymple’s time (47) a unit combined with the bay (under the name Malloodoo

and later Alcock Province) when the British North Borneo Company ruled there. (48)

Contemporary sources point to the

influence of Syarif Osman on the southwest coast of Marudu Bay. The population

of Ambong told Captain Belcher (1848: I, 194) in 1844 that Syarif Osman

exercised power on the coast between Brunei and Marudu. He demanded from them

support in the form of a ship and crew in order to help collect tribute in

Palawan, Banggi and Balabac. Syarif Osman and his fleet had made an

intermediate stop in Ambong in 1841, as mentioned by Haji Hassan, who claimed

to have seen a European woman during his stay there.(49) In all correspondence regarding

that European woman, Ambong is regarded as belonging to Marudu, which is

represented by Belcher as a large district reaching from Kinabalu to Marudu

Bay. The Governor of Singapore’s letter (Belcher 1848: I, 170) asking for clarification

concerning the woman was directed only to Syarif Osman of Marudu and not to

anyone in Ambong, where the woman was seen, or in Tempasuk, which lies in

Ambong’s direct neighbourhood. Most likely Syarif Osman’s influence on the northwest

coast of what is today Sabah would not have been everywhere in that area, but

major communities would have paid him respect and tribute.

To the north, Syarif Osman’s

influence extended at least to southern Palawan, where he demanded tribute in

the form of birds’ nests. After the Battle of Marudu, his followers established

a settlement in southwest Palawan in which they lived under a cousin of Syarif

Osman.(50) It was only after Syarif Osman’s downfall

that the Tausug managed to regain control over Balabac and southern Palawan.(51)

Syarif Osman also had relations with

the residents of Tempasuk, which he visited in 1844. Relatively independent

Iranun settled there in the eighteenth century and even referred to their

leaders as ‘sultans’. Brooke used as

argument against Syarif Osman that the Iranun were in league with him.

Certainly both Tempasuk/Pindusan and Ambong had their own leaders who, however

they may have been entitled, had regarded Syarif Osman, due to his position, as

superior to them.

According to Wright (1979–1980: 213), Syarif Osman would have

been connected through kinship to the Iranun leaders and he received tribute

from them. Pascoe (1886: 49, 51) mentioned a relative of Syarif Osman called

Sheriff Mahomed who served as parlementaire (i.e. an intermediary) and who

fought bravely but was killed:

“a fine intelligent young man about twenty

four years of age, an Illanun native (as I understood), from Mindanao in rich

attire, and head adorned with feathers”.

Even in the British reports of

1844/45 (52) it is pointed out that Syarif Osman

had been recognised by the relatively independent population of Tempasuk and

Pindusan. After all, this area was also in the coastal strip which was regarded

as belonging to Marudu. Their leaders were not as influential as Syarif Osman

since none of them managed to fill the gap left behind by Marudu’s decline in

1845.

Perhaps Marudu’s relationship with Pindusan and Tempasuk was more of an

alliance based on an institutionalised or informal friendship between the leaders,

but with Syarif Osman being considered the stronger partner in the alliance.(53)

Similarly, Syarif Osman may have had

such an alliance with Sandokong of Melapi, a leader on the Kinabatangan River.

Sandokong was in possession of the huge birds’- nest caves in the Kinabatangan

area.(54) Since Syarif Osman planned to

control the entire birds’-nest trade of the northern Borneo coast, (55) it can be assumed that he wanted to have Sandokong

under his control. Kinabatangan district is in the immediate vicinity of Labuk

district, and the existence of a good road was already reported in 1812 by Hunt

(Moor 1837: 54) to have connected Bengkoka in Marudu Bay with Sandakan which is

near the birds’-nest caves in the Kinabatangan River area.

According to oral

traditions in Marudu Bay Syarif Osman and Sandokong were comrades, and Sandokong

is said to have fought in the Battle of Marudu. He was likely to have been one

of the most influential leaders of his time.

These alliances can be compared with

the peripheral areas of the mandala concept. A supreme ruler is recognised, but

the leaders still remain autonomous in their respective areas. This alliance

area is marked on Fig. 1 as a light grey area.

The numerous alliances would

certainly have increased Syarif Osman’s reputation and power. Rutter (1922:

100) and Wright (1979–1980: 213) conclude that Syarif Osman’s de facto region

of power must have extended from Tuaran to Tungku, which lies still further away

to the east of Kinabatangan. Wright even mentions the distant island of

Tawi-Tawi. (56) However, it is difficult to prove

Syarif Osman’s sphere of influence in detail, especially regarding locations

far east of Marudu. Contemporary information indicates that he exercised direct

control over the islands and river districts of Marudu Bay and demanded tribute

even from more distant areas. His sphere of influence was likely to have been

almost exactly the area between the two ancient sultanates of Sulu and Brunei,

whose rulers looked at him not as a competitor but as connected by friendship

and kinship.

Foreign

Political Relations

As Raja of Marudu, Syarif Osman had

created his own kerajaan. He was recognised by European government officials

such as General Claveria of Manila and Governor Butterworth of Singapore, as

well as by local neighbours. Syarif Osman cultivated very good relations with

the two directly neighbouring sultanates. As already mentioned, he was married

to a daughter of the reigning Sultan of Sulu and was a friend of her brother,

the heir to the throne. Sulu had not only acknowledged Marudu, but found it a

reliable partner in troubled times. Syarif Osman was also accepted at the court

of Brunei. He was a friend of Pengiran Usop, who exercised effective control in

Brunei in his position as bendahara (that is, the chief advisor to the sultan).

Usop’s daughter was married to the Sultan’s son, the Crown Prince Pengiran Anak

Hashim. Syarif Osman also had relations with him as well as with other nobles in

Brunei. (57)

Pengiran Muda Hassim, who had been

living in Sarawak from approximately 1837/38 to 1844, (58) and his half-brother Pengiran Bedrudin travelled back

with Brooke in 1844 from Sarawak to Brunei, where they were placed by Brooke in

opposition to Pengiran Usop, because Brooke labelled the supporters of Pengiran

Muda Hassim and Pengiran Bedrudin as being pro-British, and those of Pengiran

Usop and his allies as anti-British. (59) Therefore in the British literature

of that time the alliance between Syarif Osman and Pengiran Usop is considered

as Syarif Osman’s real crime, as he thus necessarily became, in Brooke’s

opinion, an opponent of Muda Hassim and even of Brooke himself. (60) Brooke went so far as to drive out

Pengiran Usop from the post of bendahara by gunboat diplomacy (61) and to re-install Muda Hassim.

By doing this, Brooke offended the nobles of

Brunei, so they in turn finally fought against Muda Hassim and Bedrudin (both

committed suicide to avoid capture in late 1845/early 1846). Syarif Osman was well

known by those Brunei nobles who represented the real power in the sultanate (until,

that is, the situation was drastically changed by James Brooke’s intervention).

Thus, Syarif Osman had maintained good foreign relations with both sultanates, as

well as with neighbouring independent communities and with the main trading centres

in the region. In addition to Sulu and Brunei, he traded with the Iranun from the

west coast of Sabah, the Balangingi from the Sulu Archipelago, the Bugis and,

of course, the Chinese. He was invited by Butterworth to trade in Singapore

(Belcher 1848: I, 170).

He was in good contact with regional leaders; many may

have been actually present in Marudu, as indicated by the fact that after the

Battle of Marudu the British discovered many influential persons among the dead

(“persons of considerable influence”:

Talbot, in Keppel (1846: II, Appendix V, xciv)).

In the early 1840s Syarif Osman’s

authority in northern Borneo was more far-reaching than that of other leaders.

He was regarded as an ambitious and strong leader who could offer protection

and whose government was considered to be effective and successful.

THE

SYSTEMATIC DESTRUCTION OF MARUDU BY JAMES BROOKE

From 1840 James Brooke established

himself in Sarawak. To consolidate his position there he gradually eliminated

potential opponents, beginning with the leaders of the adjacent river

populations. (62)

With the move to

forcibly restore his protégé Muda Hassim to the powerful position of bendahara

in Brunei, Brooke extended his influence and intervened actively in the

politics of Brunei. Brooke had basically disposed of Pengiran Usop after

October 1844, and the Sultan was supposedly under Brooke’s control (through

Muda Hassim and Bedrudin).

Syarif

Osman as a Potential Rival to James Brooke

Around this time Brooke may have

heard of Syarif Osman’s influence in Brunei and Sulu because before 1844 he had

not written anything negative about Syarif Osman. Now he was afraid that Syarif

Osman could possibly intervene in Brunei (63) and that this could affect his

plans to bring the whole of north western Borneo under his influence.(64) Thus, Brooke began his campaign against Syarif Osman

with the reinstallation of Muda Hassim in Brunei. He was especially afraid of

the unpredictability of Syarif Osman’s reach of power. Brooke was able to

control the situation in Brunei in favour of his own interests, yet he could

not control Syarif Osman by means of Muda Hassim.(65) Marudu was a kerajaan, independent

of Brunei, and thus dangerous in Brooke’s view because Syarif Osman possessed

precisely the connections which Brooke wanted for himself. Syarif Osman had

extended his sphere of influence to the borders of Brunei and was free from the

influence of colonial powers and from control by the sultanates. The

sultanates, on the other hand, had to deal with the Europeans themselves: Sulu

with the Spaniards, and Brunei with the British. To the east of Borneo, the

Dutch were extending their influence.

Syarif Osman’s alliances with

members of the ruling families — especially Pengiran Usop and Datu Mohammed

Buyo, who were critical of European interference in their affairs (66) — might even have contributed to his reputation of

resisting European influence. Marudu’s destruction represented a preventive

measure by Brooke: the elimination of a potential opponent of the imperial

policy of expansion which Brooke wanted to enforce in Borneo. (67) With the destruction of Marudu he ensured that his own

personal leadership in Brunei and, of course, in the whole of northwestern Borneo

would not be interfered with by Marudu.

Whether Syarif Osman would ever have

turned against Brooke is questionable. He had taken no direct action against

the British when they had deposed Pengiran Usop as bendahara even though he

certainly must have been alarmed by it. Syarif Osman took only increased

defensive measures — and only after the British fleet was already in the Bay of

Marudu. Most likely, Syarif Osman did not know what was brewing against him

after October 1844, because until then he had been recognised by domestic and

foreign governments.

Because Brooke could not exert any

influence on Marudu through his good contacts in Brunei and because an

independent state could not be attacked easily, Brooke again used the ploy he

had already used successfully against the leaders of the river districts in

Sarawak. He portrayed Syarif Osman as a pirate in order to gain the support of

the British Navy, which was only allowed to intervene when the East Indian

trade routes were considered to be no longer safe. Brooke was aware of this and

was also aware that while the British and the Indian governments insisted on a

policy of non-involvement in the native states of Borneo, they would sanction activities

for the suppression of piracy. It was this issue of piracy which enabled Brooke

to obtain the naval support which was essential for the success of his wider

aims (Ingleson 1970: 38).

James

Brooke’s Campaign against Syarif Osman

Thus, Brooke started a campaign

against Syarif Osman. First, he succeeded in convincing Captain Belcher (with

whom he was travelling along the coast of northwestern Borneo after the

restoration of Muda Hassim as bendahara in October 1844) not to deliver the

letter to Syarif Osman from Governor Butterworth in Singapore, in which Syarif

Osman was referred to as “Rajah of Maloodoo” (Belcher 1848: I, 170). Brooke

persuaded Belcher to allege that Syarif Osman was a pirate. Belcher reported

(following Brooke) that Syarif Osman was planning a piratical expedition

against Palawan. Belcher’s letter of 5 December 1844, addressed to the Admiralty

— which was responsible for the security of the sea routes — is, however, in

contrast to reports in his book (1848), in which he gave a detailed chronology

of his journey. In his letter he indicates that the expedition was made by

Syarif Osman to demand tribute. After Belcher and Brooke had separated, Belcher

went on to Manila where he was informed by General Claveria that this was also

untrue, but that Syarif Osman went to a stranded ship near the island of Banggi

and took everything still usable. In his book, Belcher wrote less accusingly

and even described Syarif Osman as “the only energetic ruler” in

northern Borneo who could protect European traders.

Perhaps this discrepancy may be

traced to the temporal and spatial distance between Belcher’s writing of his

letter and of his book. When he wrote the letter dated 5 December 1844 he was

still under the influence of James Brooke’s statements. On his part, Brooke

wrote at that time about the piracy of Syarif Osman in letters to Wise (CO

144/1, 31 October/5 November 1844). It was imperative for him that other persons

represented Syarif Osman as a pirate — so Belcher’s letter to the Admiralty was

of great significance to Brooke. A start on the systematic defamation of Syarif

Osman had been made.

In February 1845 Brooke went on the

offensive, after having received — through Captain Bethune — his official

appointment as ‘Agent near the person of

the Sultan of Brunei’.

Since the beginning of his operations in Sarawak,

Brooke had hoped to be officially recognised by the government in London. Now

Aberdeen (that is, the Foreign Office) had granted him this unpaid office and

also informed the Sultan of Brunei in a letter that Brooke was now officially

allowed to conduct negotiations for the United Kingdom. Brooke was to ensure

Brunei’s cooperation in the protection of trade.

Bethune was instructed to send the

Foreign Office letter to the Sultan and to look for a suitable site for a naval

station in north western Borneo. Labuan was under discussion since it was

halfway between Singapore and Hong Kong and it promised to have coal resources.

Brooke supported the idea of having a British colony on the island of Labuan,

partly because it could serve to control Brunei. So Brooke and Bethune travelled

to Brunei, where they arrived on 24 February 1845 and immediately met with the

Sultan and other nobles. Brooke prepared a memorandum for the British government

in which he outlined the advantages of Labuan and the need to eradicate piracy,

in particular the elimination of Syarif Osman. Only one day after his arrival in

Brunei, he persuaded the nobles to sign a letter requesting that action be

taken against Syarif Osman because official procedure required that notice of

this concern be conveyed by the Brunei Government to Brooke. (68) In Brooke’s diary, the following statement is dated 25

February 1845:

“The

rajahs of Borneo have addressed to me the following letter, in my public

capacity, which I conceive will be sufficient to gain protection for Borneo, if

it does not enable the authorities to act in the offensive, and at once to

crush Malludu and its pirate gang” (Mundy 1848: II, 15).

Strangely, this letter from the

Sultan and Muda Hassim to the Admiralty was dated 6 March 1845. The reason for

post-dating it to 6 March can be explained by another event. On 5 March Brooke

wrote:

Received intelligence from Malludu:

Sheriff Osman has fortified himself, and is prepared to resist the threatened

attack of the English; and report further states, that if the British squadron

do not attack him, he will, at all events, assault Brunè for having entered

into a treaty with us. Throwing aside all speculative points, our first

endeavour must be to crush the Sheriff, or at any rate to protect the capital

(Mundy 1848: II, 29).

The exact message received by Brooke

is an open question. Certainly it was not as dramatic as he described it.

Marudu was already known as a strong fortress. If Syarif Osman had threatened

Brunei then he was most likely referring to Brooke’s protégés Muda Hassim and

Bedrudin and not to the Sultan or Brunei itself. Brooke took this message as

the reason to newly date the letter from the Sultan and Muda Hassim, which he

had actually received 13 days earlier, to make it more obvious why the Brunei

authorities would seemingly ask at this point in time for the protection of the

British against Marudu. As Marudu and Brunei were previously allied by flourishing

trade and friendly bonds, it is questionable whether the Sultan had signed this

letter voluntarily.

In February/March 1845, Captain

Bethune’s ship was at anchor in Brunei and thus potentially threatened the

Sultan and the nobles. This letter was very important for Brooke’s plan to win

the Navy’s support for an offensive against Marudu. So he handed the letter and

Bethune’s and Belcher’s statements against Syarif Osman to Vice Admiral

Cochrane in Singapore, where he had gone together with Bethune after his stay

in Brunei. The Navy officials relied on Brooke’s information since they

believed he had insight into the local situation, and because he could also provide

them with local complaints about Syarif Osman. Thus Brooke managed to win the

Vice Admiral’s support for his projects in Brunei and Marudu.

Vice Admiral Cochrane also addressed

a detailed letter to the Admiralty. He presented letters from Captains Belcher

and Bethune as well as the Sultan’s letter dated 6 March 1845. Brooke,

recognised as an Agent by the Foreign Office, sent in turn a copy of the same

letter from the Sultan, as well as his two memoranda to the Foreign Office

(Memorandum on the Suppression of Piracy and Memorandum on the Royal Family of

Borneo, both dated 31 March 1845, FO 572/1, No. 7). He also sent copies of the

Sultan’s letter and of the first-mentioned memorandum (on piracy) to Governor

Butterworth of Singapore. This letter campaign was based on Brooke’s misrepresentation

of Syarif Osman as a pirate and a danger to the security of Brunei and, more

specifically, to British interests in Brunei.

The

Charge of Piracy

In these letters, Brooke tried to

provide evidence of the offence of piracy. In his documents of 1845 he

mentioned three ships in particular: the Sultana, the Lord [Viscount] Melbourne

and the Wilhelm Ludwig. In mentioning these ships, Brooke was attempting to

associate them with acts of piracy. In fact, they were shipwrecked.

The Sultana was shipwrecked on 4

January 1841 in the vicinity of Dumaran Island, which lies northeast of

Palawan. Most survivors were able to make it to Brunei, where they were robbed

of their possessions, taken prisoner and treated as slaves.

However, nineteen

people landed in Marudu. One of them, Haji Hassan, said:

“When at Maloodoo, I lived in

the house of a Syed, and was treated very well” (Belcher 1848: I, 165).

He only stayed there a few days before he travelled to the south with a crew

from Marudu and stopped in Ambong, where he saw a European woman who lived

there (Singapore Free Press, 30 September 1841). In October 1844 Governor Butterworth

asked in a letter — which by Brooke’s instigation was not delivered — for

Syarif Osman’s assistance to resolve the case with regard to the European woman

in Ambong.

Butterworth makes no mention of

possible Sultana crew members enslaved. He could have asked Syarif Osman for

their release if it was assumed that they were still staying in Marudu.

However, in June 1845 in Singapore, Brooke had Church, the Resident Councillor,

prepare two testimonies of former Sultana crew members in which they reported:

We are there seized and detained by

Shireef Osman, the chief of the place, who treated us in every respect as

slaves. After a time, myself and Mahomed, here present, were handed over to

Dattoo Bureedeen, of Marudu. We remained there about two years, when the Dattoo

conveyed us and Jose the drummer to Borneo, and handed us over to Pangeran Usuf

(PP LXI, 1852–53, Cochrane to Admiralty, 21 July 1845, Sub-Enclosure 2,

Statement of Bastian Martinez).

These statements were sent to the

Admiralty in London to provide evidence against Syarif Osman and, of course,

also Pengiran Usop. However, first, it is quite strange that Brooke obtained these

statements exactly at that point when he desperately needed to persuade the

Vice Admiral to fight against Pengiran Usop and Syarif Osman; and, secondly, even if things were as the two

sailors testified, the fact of slavery was still no proof of piracy. The

British, and also Brooke, knew that shipwrecked persons automatically became by

law the property of the finder. (69)

The same weakness of a claim of

piracy applies to the shipwreck of the Lord Viscount, which ran aground on the

Luconia Shoal off the coast of Brunei on 5 January 1842. Here, Captain

Bethune’s only accusation is that Syarif Osman had sold the sailors into

slavery. (70) In 1842 twenty crew members were

held in Brunei, but eventually they were handed over to Brooke, who did not

connect their fate with Syarif Osman, but with Usop. With the case of the Lord

Viscount, as with the Sultana, neither Brooke nor Bethune went so far as to

construct a possible pirate attack by Syarif Osman.

The third ship, the Wilhelm Ludwig

from Bremen, became stranded — unlike the other two ships — in the waters of

Marudu itself, on a small island called Mangsi, probably in October/November

1844. According to Brooke, the alleged looting and burning of this European

ship was the answer of Syarif Osman to Muda Hassim’s demand that he must not

come to Brunei any longer and was a deliberate continuation of his pirate

deeds. (71)

However, General Claveria explained

to Captain Belcher in Manila at the end of 1844 that Syarif Osman had gone

there to take the salvage left behind by the crew. In fact, it was unwritten

law in Southeast Asia that the salvage belonged to the ruler on the spot. (72) After the Battle of Marudu, a ship’s

bell, furniture and anchor chains from the Wilhelm Ludwig were found, but these

came not from a pirate attack — as Brooke had claimed in August 1845 (73) — but as salvage of an already abandoned ship in

Marudu. In none of the cases — not the Sultana, the Lord Melbourne nor the

Wilhelm Ludwig — can acts of piracy by Syarif Osman be proved.

Brooke and the British Navy officers

influenced by him had no evidence, a fact which Belcher also noted:

“Serif Osman ... never engaging himself in

any active Piracy he encouraged the real actors in every possible way supplying

arms and food, and assisting in the disposal of the plunder” (CO 144/1,

Report on Balambangan, p. 64/ archive numbering).

However, Belcher claimed — as did

Brooke — that Syarif Osman had practised indirect piracy. But if they adopted

this stance, then they logically should also have charged with piracy all those

persons involved in this type of trading system, including the majority of

Malay and Borneo nobles! Syarif Osman participated in the trading system and,

of course, in slavery in a similar manner to other nobles of Sulu, Brunei and

other places. When it suited his purpose, Brooke, on the one hand, tolerated

this kind of cooperation with alleged pirates, while, on the other hand, he

readily used it as evidence against someone who was standing in his way. He had

no real evidence of active piracy by Syarif Osman, so he tried to create a

picture of Syarif Osman as a pirate by citing the cases of the three ships.

Brooke seemed to have a very

thorough knowledge of what constituted piracy but he was unwilling to accept

the legal results attributed to the definition. Hence, he redefined the concept

of piracy in order to rationalize some of his illegal activities. They [Brooke

and the British Navy] distorted the legal term to fit the forces of the Borneo

states and thus to justify attacking them. To suggest that James Brooke did not

know the legal definition of piracy in international law is to insult his

intelligence (Hamzah 1991: 15, 18).

In April 1845 Cochrane had promised

to support Brooke, who now urgently awaited his support as he feared that the

situation could escalate in Brunei. Muda Hassim was not nearly as popular as

Brooke tried to make out to the authorities. He was afraid that Pengiran Usop

might seize power with support from Syarif Osman.(74)

In May 1845 he

again went with Bethune to Brunei, where they learned that in the meantime the

American ship the Constitution had anchored in Brunei waters and the Americans

had tried to enter into trade relations with Brunei but had failed to do so due

to translation difficulties.

This provided a further argument for

Brooke to urge the authorities to intervene. In the official correspondence

with Aberdeen (the Foreign Office), Brooke stressed that the visit of the

Constitution had weakened the pro-British side. In addition, he pointed to

possible interference by the French who showed interest in Basilan Island in

the Sulu archipelago. When he corresponded with the Foreign Office, Brooke did

not use the charge of piracy as his main argument because the Foreign Office

did not have jurisdiction over piracy matters, so he instead emphasised concern

about the security of the British sphere of influence in Borneo, which could be

threatened by the Americans or the French.

Bethune and Brooke travelled

immediately from Brunei to Singapore to promote their cause. Here they asked

Church, the Resident Councillor, to record the testimonies of two former slaves

from the Sultana who had travelled with them to Singapore. He could have

recorded the statements previously when they were all in Brunei where Brooke

had obviously ransomed them,(75)

but it looked more

official if Church recorded them. Brooke used these statements for another

letter campaign in June/July 1845. Again he wrote to the Foreign Office, while

Cochrane sent to the Admiralty a letter with many enclosures which he had

received from Brooke. However, when Cochrane wrote his letter on 21 July 1845

he must have known that it would reach London only after he would have

intervened in Brunei and Marudu. Thus, their letters were only directed to

obtain ex post facto approval of their operations.(76)

The

Offensive against Pengiran Usop

Cochrane set out for the northwest of

Borneo with eight heavily armed ships. Such a fleet brought fear and terror to

the Siamese: upon departure of the fleet from Malaya, the Siamese immediately

took preventive defensive measures because they assumed they would be attacked.(77) Cochrane and Brooke arrived in

Brunei on 8 August 1845 in order to proceed against Pengiran Usop. Officially,

he was accused of having held British subjects in slavery. The Sultan and other

nobles could also be similarly accused of slavery, but Brooke did not want to

eliminate them at that time. The later secretary and biographer of Brooke,

Spenser St. John (1879: 101), saw it as fortunate that two British subjects

were held as slaves by Pengiran Usop because that provided a pretext for

Cochrane to proceed against Usop.

The Vice Admiral again got the

Sultan’s written approval for his planned action and he persuaded the Sultan to

declare that Usop was rebellious and would probably attack the pro-British

party after the British had departed. There is no doubt that the ships in

Brunei’s waterways intimidated the Sultan so much that he had no choice but to

sign the document.

Following Brooke’s statement, it was

demanded that Pengiran Usop should appear before the Sultan unarmed and in the

presence of British soldiers, otherwise the British would attack his residence.

He had one day to comply. According to the statement of Edward H. Cree, the

surgeon of the Vixen who was present in the negotiations, Usop took part in the

first meeting but refused to sign a British contract to suppress the piracy,

whereupon they gave him one day to sign, otherwise they would fire upon his

house (Levien 1981: 156). Usop then barricaded himself in. Expecting a violent confrontation,

the people fled. Cree describes how a shot was fired through Usop’s roof, which

the British considered a warning.

The Pengiran defended himself and

then shot back in turn. The British, however, claimed that he had started the

fight because their first shot was only a warning. Thus, they were able to

justify the destruction of the house. The first shot was a heavy hit and, of

course, the British had opened the attack with it, but later authors followed

the opinion of the Vice Admiral that Usop had attacked first.(78) Usop was put to flight and his

influence destroyed in Brunei. He returned after the British had departed and

tried to fight Muda Hassim and Pengiran Bedrudin, but they put him to flight

again. Usop escaped to Kimanis, which belonged to him as Sungai Tulin

(inheritance). Brooke later urged the Sultan to impose the death sentence on

Usop, which was enforced in October 1845.

The

Battle of Marudu

Cochrane’s fleet left Brunei and

reached Marudu on 17 August 1845. The Vixen, Pluto, Nemesis, Wolverine and

Cruiser sailed deep into the bay. Cochrane gave the command to Captain Talbot.

With 24 boats loaded with guns, he went to Syarif Osman’s position. Talbot was

to fall back if victory was endangered. The British did not know Syarif Osman’s

exact position, but were led to him by two Brunei natives who — according to

Cree (Levien 1981: 161) — acted under duress. Early in the morning of 19 August

1845 Talbot entered the river leading to the fortress. The pilot failed to

inform the Captain of the full situation as he overlooked the fact that one

sideof the fort was accessible by land; here Talbot could have sent soldiers.

Syarif Osman’s position consisted of

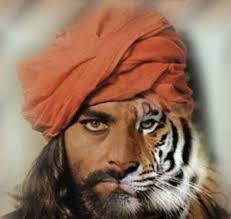

two forts, one equipped with three cannons,the other with one (see Fig. 2). The

forts, separated by a creek, were decorated with colourful flags, a sign of the

presence of many distinguished leaders and personalities.Syarif Osman’s own

banner — a red flag with a tiger’s head — flew over the fort.(79) He had placed a barrier made of tree

trunks and iron across the river about 200 metres ahead of his fortress so that

enemy ships could not proceed, but the gunners of the fort could fire on the

attackers.

Before the battle commenced, Syarif

Osman had sent Syarif Mohammed with a flag of truce and asked for negotiations,

but the British did not agree. The British began to work on the barrier with

axes, whereupon Syarif Osman opened fire. The battle took about an hour and

claimed nearly ten dead and twenty wounded on the British side. Cree describes

how a squad of soldiers landed on the right-hand river bank and successfully

targeted the fortress with rocket projectiles (Levien 1981: 161). These weapons

might have been superior to those of Syarif Osman and caused havoc in the fortress.

The only chance of the Marudu defenders lay in the persistent bombardment of

the barrier to avert an assault. However, after firing they had problems in

bringing the guns back into position (according to Pascoe).(80) When the British broke through after

an hour, most of the defenders fled. There was some hand combat, but the battle

had already been decided. Probably the loss of skilled combatants by the rocket

fire.

A. Enemy’s stockade.

1. Eight-gun battery.

2. Eight gingalls (large, often mounted, muskets).

3. Burial ground.

4. Serip Usman’s house.

B. Three-gun battery.

C. Floating battery.

D. Double boom made of two tree trunks, one 7 feet and the other 5 feet in circumference, fastened to each launch by an iron chain.

E. Jungle that had been cut down and undergrowth about breast high.

F. Gardens.

G. Malay town.

H. High jungle.

1. English force.

2. One Rocket battery.

K. Boats — 21 in number, eight of

them with guns.

1. Agincourt’s launch.

2. Vixen’s pinnace.

3. Daedalus’ launch.

4. Vestal’s launch.

5. Agincourt’s barge.

L. Small ditch which before the

action was supposed to be a deep branch of the river. (Levien 1981: 158)

Ground plan of the attack on Marudu was

too high for a more effective defence. A report in the Straits Times in October

1845 (Vol. 1, no. 1, p 2) states that 240 fighters from Marudu were killed and

wounded:

“The slaughter has been very severe ....”

The Britons found many prominent

leaders among those killed, but Syarif Osman was not found. Cochrane suspected

that he had fled to his small house in the countryside. The British assumed

that he had been wounded. He did not show up again in the history of Borneo.

Therefore Cochrane and Brooke assumed that he had died when they controlled the

location a year later. (81)

After the flight of the defenders,

the British fell upon the location, sacked, killed, and set fire to the fort,

burning down (to their own anger) some camphor warehouses. The British even ran

the risk of being trapped by the fire. They made the guns unusable or took them

on board their ships.

The sailors and marines chased after

them [the Marudu-defenders] in such an unruly manner that one of the officers,

Lieutenant Pascoe of the Vestal, was disgusted: ‘all was helter-skelter as if

going to a fair’, he said later. The navy had done a great deal of damage with

gunfire and there were many dead and wounded, but some of the sailors and

marines treated the whole affair as a great lark (Evans 1978). Finally, the

British caught some animals and ended their operation with a picnic.(82) People who searched for possible

survivors a day later in the ruined fortress were expelled as looters with a

few shots. Brooke and Cochrane tried again to justify the destruction of Marudu

as a pirate hideout through physical evidence. They took the ship’s bell of the

Wilhelm Ludwig, which they had found in Marudu, as evidence of piracy, although

it was made clear by Belcher that the bell had come to Marudu as salvage.

As a result of Brooke’s defamation

of Syarif Osman, Marudu was destroyed on Cochrane’s command. Based on

constructed evidence, Cochrane and Brooke won approval for the destruction of a

flourishing trade centre in northern Borneo. Marudu had fallen victim to the

preventive measure of Brooke, namely, the destruction of a potential opponent

of imperial expansionism and of his own claim to leadership in north western

Borneo.

However, the charge of piracy was so

massively driven by Brooke that it has repercussions to this day. On 19 August

1845 he not only caused hundreds of people to lose their lives and destroyed

their settlement, but he also destroyed the memory of the real Marudu. Clearly

it was not a pirate hideout and Syarif Osman was not the powerful leader of

Borneo pirates, but a raja who was about to build up Marudu as a kerajaan

(kingdom), independent of Sulu, Brunei and other regional powers. The significance

of what Syarif Osman achieved in Marudu is in large part lost or has been

ignored.

“Thus has Marudu

ceased to exist.”

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------

(1) Keppel (1846: II, 152).